Medical History: Changing the faces of war in France

How many soldier faces were disfigured in the war field? How could soldiers return to “life as usual” when their faces are no longer there? Amidst the horror of injuries, improvements in prosthetics were achieved.

How many soldier faces were disfigured in the horrors of the war field? 10,000? 14,000? Besides the thousands of dead, WWI often left deep physical suffering for many survivors. How could soldiers return to “life as usual” when their faces are no longer there? Amidst the horror of injuries, improvements in prosthetics were achieved, helping the lives of many beyond the post-war years.

The author, Jean-Christophe Piot, mixes historical facts and storytelling to reveal some of the most striking events in the history of medicine. You can check his previous articles on cholera in London, “body snatching”, the “K syndrome” or syphilis. Made in cooperation with our partners from esanum.fr

This article contains images that some users may find distressing. Viewer discretion is advised.

In the summer of 1914, many went to the frontline convinced that the conflict would be short. That autumn, however, the Western front remained locked for three years in a war of trenches, positions, and pyrrhic gains. Artillery, the main cause of death and injury (estimated at about two-thirds of the total) was the main “protagonist” of this war. A "storm of steel", to use the title of Ernst Jünger’s book (original German title: Stahlgewittern, 1920), brought about a new dimension to war medicine, with types of wounds and sheer scales of wounded victims, that had never been seen until that period. A grim medical challenge emerged: the large-scale care of facially disfigured soldiers.

Of the eight million soldiers mobilised by France between 1914 and 1918, 1.4 million were killed. Twice as many were affected by injuries of varying severity, and between 11 to 14% of them had facial injuries. Impacts could be direct, caused by grenades, bullets, shrapnel balls, shrapnel, or indirect, caused by wooden splinters torn by explosions from the parapets holding the trenches in place, or by metal fragments from their own helmets.

On the evening of November 11th 1918, France alone counted between 10,000 and 14,000 soldiers seriously wounded in the face and head. Never before had a conflict left such injuries on the bodies of combatants. The Crimean War and then the Civil War, with its first use of machine guns, had only just scratched the surface of the real world implications of the mechanised and industrial violence that characterised the Great War.

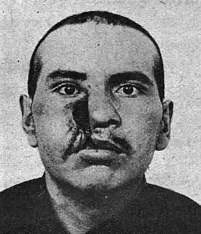

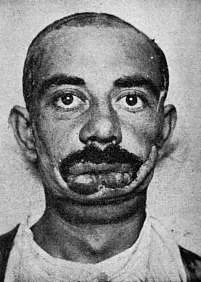

A whistle, and nothing more

For these men, aged between 18 and 40, the consequences of the conflict in their bodies were without precedents in their brutality. Their jaws and teeth were swept away, cheekbones broken, ears, nose and eyes torn off, facial bones sunk and deformed. When questioned, most of them evoked a vague memory of a whistle or a detonation, before an almost systematic loss of consciousness. In addition to the purely physical trauma and the unbearable pain they felt when they woke up, they were also aware of their new state, of their devastated face, which almost inevitably caused their friends and even their caretakers to step away in shock.

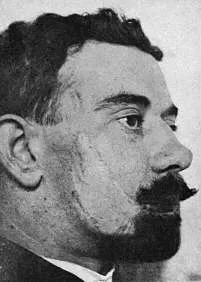

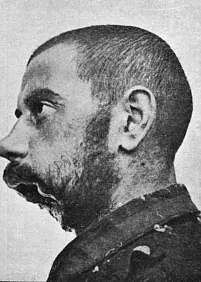

In Versailles, at the signing of the Treaty, then French Prime Minister George Clémenceau was allegedly so surprised by the horror of the wounds he saw that he uttered to a soldier: "You were in a bad corner, it shows!” («Vous étiez dans un mauvais coin, ça se voit!»). The spectacular wounds of the "broken mouths" are frightening. The expression comes from Colonel Picot, who uttered the phrase in a moment of anger when he was refused access to a seminar for disabled soldiers at the Sorbonne.

Colonel Yves Picot (1862-1938)

If this reaction (as humiliating as it was deeply unjust for these men who had done their duty) is shocking today, it was not uncommon in the post-war period. "Forgotten" for official gatherings or placed on the sidelines, banned from entering certain shops, cafés and brothels1, these wounded men, who were so peculiar, were by their very appearance a symbol of the Roaring Twenties in the France that was once again rediscovering the joy of life. But it is undoubtedly in the family circles and social environments that these faces of war forever changed the day to day routines of those close to the wounded.

Henriette Rémi, a Swiss nurse who worked in a dispensary for the seriously wounded during WWI, left behind several unbearable testimonies given by these men who no one could recognise any more. And this shock began with their wives and children. The case of a certain Lazé, a teacher by profession, is an illustration of this.

Lazé was hit in the nose and eyes by a shell and was left blind. He healed, however, little by little, and was allowed to visit his family and his little boy. At the door, the little boy ran towards his father - and stopped frozen before taking refuge back in the house, shouting "Not daddy, not daddy!”.

Lazé was sorry, described Henriette Rémi; the boy was trembling, as was his father. His wife commented to him: "You were too quick, you should have taken precautions." He took his head in his hands and moaned: "Idiot! Idiot! But how could I have known I was so awful to see? Someone should have told me!" And Henriette concluded her own thoughts on the episode: "Despair and shame seized me. Yes, he was right. At the hospital, we had only one desire: to convince them that they weren't so terrifying, but now look at the result".

Back at the hospital, the veteran collapsed: "Having once been a man, I am now a monster, an object of terror for my own son, a burden for my wife, a shameful thing for humanity.” That same evening, Lazé committed suicide by slitting his wrists open with his penknife.

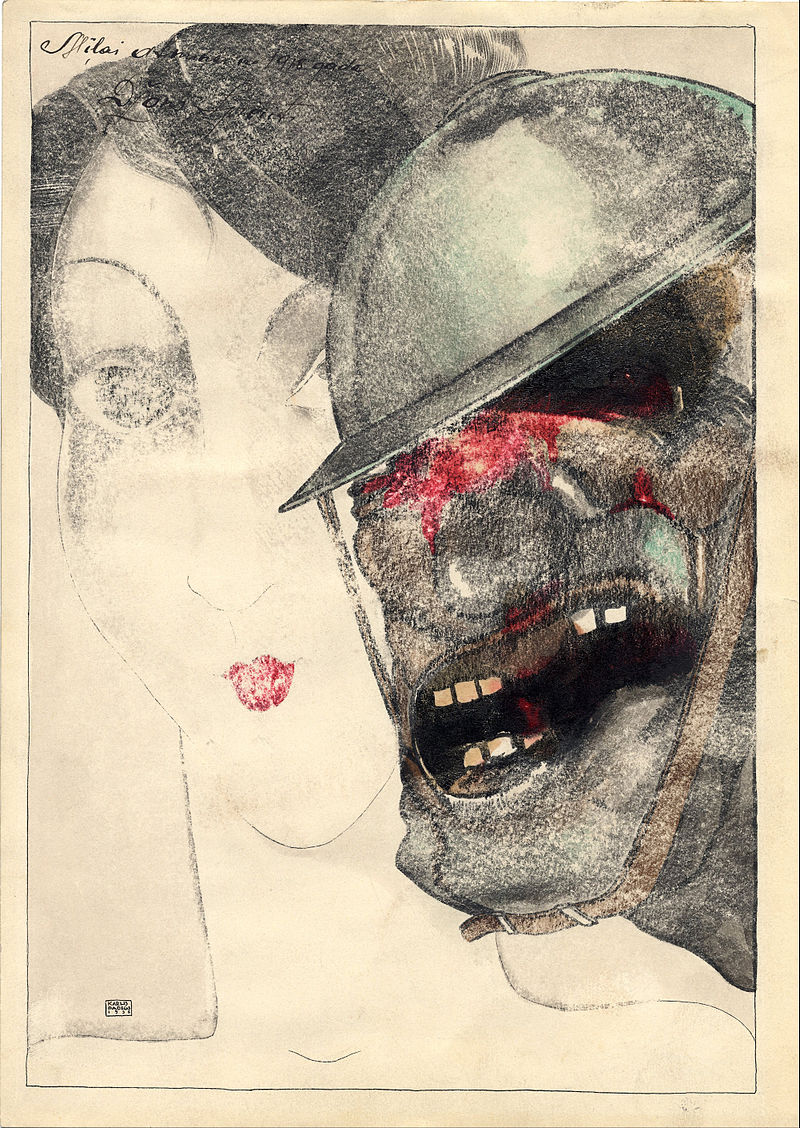

Memento From 1918. John Yperite" (Karlis Padegs, 1935)

Reconstructing faces

On top of the despair suffered by the wounded, there is the caregivers’ distress. However, this does not prevent them from looking after the injured, whose injuries do not only change the geography and the appearance of faces. Even before their psychological consequences, they pose a real challenge to the surgeons when it comes to reconstructing what can be reconstructed, in order to restore the patient’s ability to swallow, express themselves, and even breathe, if not normally, at least more easily.

Such is the challenge of a treatment which often requires a double surgical and prosthetic treatment. Although no specific care was provided for face wounds until 1925, when parliamentarians adopted a "disfiguring injury" category, these ex-servicemen were very quickly treated separately from the other wounded, from the very beginning of the conflict. The nature of their wounds and the length of time required for their care partly explains this. But it was also a way for physicians to protect these men from the eyes of others, even if it meant encouraging the emergence of a form of confinement and withdrawal. Amidst the isolation however, developed nonetheless a very powerful feeling of solidarity between patients, too.

What do these wounds and their treatment look like? In simple terms, the face wounds left by WWI artillery warfare provided a paradox. On the one hand, they seemed spectacular and dantesque; often the rescue personnel and stretcher-bearers probably left men behind who could have otherwise been saved, as the wounds were so severe that their sufferers were assumed dead on the spot. But instead, face wounds are particular in that they, in fact, occur in an area with less dense vascularisation and the little fatty tissue, limiting the risk of infection or gangrene caused by gas-based weaponry. Despite the sight, face wound treatment would translate into a higher chance of patient survival.

Once the emergency issues have been treated (i.e. clearing the airways, controlling haemorrhages, etc) treatments for facial wounds began diversifying as more and more patients entered the emergency and recovery hospital wards. At first, they were welcomed in the Paris region in rapidly overcrowded units such as the Val-de-Grâce or Lariboisière hospitals. They were then sent to new services created throughout France: Bordeaux, Amiens, or Lyon, the latter of which rapidly developed a renowned expertise in these types of wounds thanks to the collaboration between stomatologists (a.k.a. Oral medicine), surgeons and their colleagues from lyonnaise dental schools.

The medical response developing at the time was divided into three main fields: appliances, surgical grafting and prostheses; but the first progress was in the field of anaesthesia. The classic techniques employing ether or ethyl chloride were not suitable for surgery on the mouth and face, since they require the anaesthetic mask to be worn during the operation. Anesthesiologists had to therefore develop new methods, starting with intravenous routes.

Painful appliances

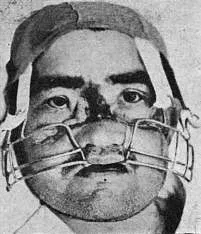

The first type of treatment, orthopaedic devices, were intended for the least complex type of injury. In the case of fractures or displacements, physicians preferred to immobilise the compromised bones, close any wounds that may be present and use ligatures, orthodontic bows or dental aligners to support or replace what is left of the jaws. Mouth openers were also used to stretch the remaining muscles and regain elasticity.

Some injured people had to use masticatory devices all their lives, others wore the so-called “Darcissac’s helmet” for several weeks, which is relatively effective in replacing the bone structure but extremely painful and tiring. The injured constantly had their mouths open for three to four weeks, resulting in permanent salivation, which earned the specialised hospital section in Val-de-Grâce the charming nickname of "drooling unit" (“Service des Baveux”).

There was another instrument, very quickly perceived as a torture device by patients, who were often unable to complete the treatment: the bag procedure (“le procédé des sacs”). Created in 1916, it consisted of placing wooden plates in the mouth, before hanging bags to put the mouth back in its normal position. The bags could weigh up to three kilos.

From ancient to modern grafting

Maxillofacial surgery concerns patients whose face must be reconstructed in depth, to enable them to regain such fundamental functions such as chewing, swallowing or phonation. Whether it is surgery in the strict sense of the word or surgery associated with prostheses, the challenges are immense in cases of destruction and loss of bone and muscle substance, which up until then were still rarely seen.

Osteoperiosteal grafting of bone parts has been known for some time since 1914. Progressively adapted and specialised, it consists of taking a fragment from the tibia, rib or scapula of the injured person to make a malleable graft, capable of filling the wound cavities, regaining a certain bone continuity and correcting at least large sections of the most spectacular facial deformities.

For the softer parts, two main techniques were to be used and often combined to obtain a similar effect on the flesh. The first, known as "Italian grafting", was mentioned as early as the 15th century by the Italian physician Tagliacozzi, who was eventually nicknamed the "surgeon of miracles". His masterpiece text “Chirurgia nova de nasium, aurium, labiorumque defectu per insitionem cutis ex humero” earned him an excommunication by the Catholic Church. The technique consists of taking a flap of skin from the patient's arm and placing it on the facial wound to gradually close it. The constraint is enormous: in order to allow continuity, vascularise the gap and allow the wound to close, the arm must be kept close to the face for a good fortnight with the help of a metal structure, all at the price of the pain and discomfort one can imagine.

The second, developed by surgeon Léon Dufourmentel at the end of WWI, provided better results. This time, it consisted of taking strips of scalp from the patient's skull and grafting them onto the face, essentially towards the chin. Rejections were rare, there was less risk of retraction, and the flesh patch that is created little by little provides the face area a semblance of a"normal" shape, with fatty sections sometimes filling the remaining cavities.

A diversity of prostheses

Then came the prosthetic treatment. The first objective was a functional one, and here again varies extensively depending on the injury; it is essentially to replace or complete the jaws and teeth that have been removed. Rubber, light metal, porcelain, early plastics: advances in materials made it possible to explore new avenues with removable or fixed prostheses (crowns, bridges, etc.), and above all, the creation of new solutions that were less unpleasant to wear.

The aesthetic aspect was also essential for men who have at this stage endured considerable physical suffering and had to face the judging gaze of others. In the final phase of reconstruction, false eyes or false noses were often combined with accessories, such as glasses or beards, to cover part of the damage and mask the pinkish or shiny appearance of the healed and reconstructed skin. Some injured people, too bothered by these accessories and psychologically able to cope through the situation, opted instead for simple bandages or assumed their new appearance, the naked face.

Drawing faces

Some of the "Broken Mouths" would use masks like those made by Ana Coleman Ladd. Under the support of the Red Cross, the American artist opened the "Studio for Portrait Mask'' in Paris in December 1917. This was a mask workshop that she designed and where she drew herself. Ana Coleman Ladd was not a physician; however, she was one of the first people to defend a principle that would become essential in the field of aesthetic prostheses: the importance of getting as close as possible to the former appearance. "A mask that does not resemble the man as he was known to his relatives would be almost as harmful as the mutilation itself”, she would state about her approach.

It is not a question of hiding but of finding a face. This meant spending time with each patient, discussing, understanding how they felt, what they were hoping for. She also asked them to bring photos of them before their injury - the one in their military booklet most often, sometimes their wedding photos. Then came the moulding, first with the print of the disfigured face and then the reconstitution by modelling pre-war features in clay.

The mask is then made by electroplating: the moulding is immersed in a bath of copper sulphate through which an electric current is passed. The thin copper plate obtained weighs a few grams. By covering it with enamel paint, the artist seeked to reproduce precisely the colour of the skin and the appearance of the face that had disappeared. The details - eyebrows, eyelashes, moustaches - were sometimes made with real hair.

Click the image above for video footage of Anna Coleman Ladd's Studio for Portrait Masks in Paris (External Link)

Ana Coleman Lad's initiative - encouraged by Léon Dufourmentel, the precursor of maxillofacial surgery - would last two years. Jane Poupelet, a French sculptor who joined the Studio, would later confess how much she was impacted by her work at the studio. "After having seen so much pain, I would never sculpt as I did before", she expressed.

Hundreds of mutilated people would be benefited from their work, even if the purely aesthetic solution was not perfect: the faces aged, not the masks nor the prosthetics. The copper plate gave soldiers a fixed appearance, condemning them for life to the same expression.

Some of the wounded ended up giving up wearing these masks, which sometimes got damaged after a few years of wear. But they played a crucial role. In the letters of gratitude that reached Ana Coleman Ladd wrote, one soldier would write: "Thanks to you, I will have a home." Another would confide to her: "The woman I love, no longer finds me repulsive, though she had the right to do”.

Note:

1. A small but certainly picturesque side to the events: some famous brothels, such as the “One-Two-Two” in Paris’ 8th arrondissement, adopted the opposite policy by reserving certain evenings of the week for these veterans.