Medical History: “Body snatching” in Europe

A recent scandal on donated body parts at a French university sparks a look back into the history of anatomy research in Europe and how social, economic, scientific, and legal dynamics shifted through the centuries.

A look at the early stages of European anatomical research

A recent scandal on the management of body parts at a French University provides an interesting opportunity to look back at the history of anatomical research in Europe and how social, economic, scientific and legal dynamics have shifted through the centuries.

Poor preservation conditions, disrespectful treatment of the deceased, trafficking in anatomical parts… With the temporary closure of the Body Donation Center (in French: “Centre du Don des Corps”, or CDC), the scandal in the winter of 2019 at the Descartes University, Paris, highlighted the sensitive nature of body donations to science; in particular, the case of remains intended for dissection. This scandal provides an interesting opportunity to look back at the history of anatomical research in Europe and how social, economic, scientific and legal dynamics have shifted through the centuries.

A practice that is essential for the research and training of future physicians, and yet one that had been more or less clandestine over the centuries, the gathering and exchange of corpses has always had its supporters and opponents. But it rarely equaled the heights of macabre surrealism reached in England between the 18th and 19th centuries. This was the age of “body snatchers”.

Despite the precise definitions and extensive published resources on anatomy, most physicians may agree that before you can understand how the human body works, you have to tinker with it. But prior to that, you have to make your mind up on that decision. Yet, forced by social and religious taboos, the history of anatomical research is a continuous back and forth between the ambition to learn more about how the human body works, and how a community looks at death and its social acceptance of such research.

There is somewhat of a consensus that it was in Alexandria, Egypt, that the first traces of medical dissections were found under the scalpel of Erasistratus or Herophilus. It is also accepted that anatomy almost disappeared afterwards. Galen himself, who certainly had the opportunity to study anatomy while treating wounded gladiators in the arena, was probably unable to perform dissections, which were prohibited in Roman law at the time. His alternative: to extrapolate his studies of the human body by practicing on great apes.

Clandestine activity reigned anatomical research until the birth of the first European universities in the 13th century. The first dissections done as part of medical education began in Bologna and then in Montpellier around 1340. It wasn't long before André Vésale, in the early 16th century, gave birth to a true anatomical science.

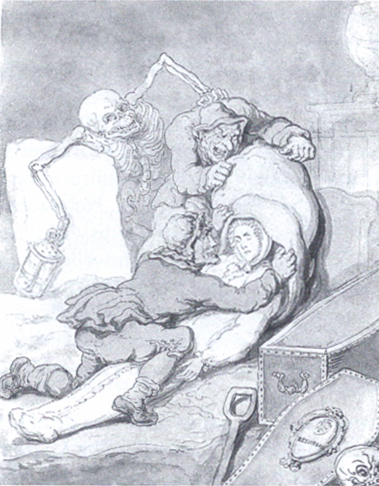

Resurrection Men by Thomas Rowlandson

Body scarcity

Even if aim to practice a legal and open setting for didactic purposes, dissections quickly face a first major hurdle: finding the body. In Europe, the Catholic church never forbade the practice as such, but the conditions that guide civil and religious authorities to approve physicians’ dissections may vary, albeit they are always drastic. Generally speaking, there had been a window of availability from the remains of executed criminals, but in here lies a scientific disparity: they are essentially male bodies, often damaged by the conditions of imprisonment or the mode of execution employed1.

In the 1300s, at a time when European medicine was beginning to surpass the volume of wisdom accumulated by the great ancients like Hippocrates and Aelius Galenus, the great challenge to advancing knowledge was the supply of bodies or body parts. Furthermore, anatomists lacked fresh bodies to train with, as their availability for postmortem soon after an execution was impeded by complex procedures. Eventually, England became a pioneer of body supplies for anatomical research, a process that occurred in two stages, and, it seems, by chance.

The first stage occurred by 1688. At the time, the kingdom applied one of the most repressive penal policies in modern history: the Bloody Code, a penal system that applied the death penalty to an extensive number of offenses, that at its peak reached some 220 crimes punishable by death. At times, these included the theft of cattle or horses. During the implementation of the so-called Bloody Code, executioners had a spike of activity, and amidst this context, academic centers at the time raised the volumes of requests for bodies or body parts following the implementation of death penalties. But even then, the granting of bodies from the penal system to researchers was not an easy process.

Then came the year 1752. With the Murder Act, King George II decided that murderers were not to have a typical burial after their execution. As a form of public deterrence, the legal texts now provided two possibilities, that were up for the judge’s discretionary choice on what to do with the bodies of the executed: A body could be exposed in a cage, suspended from gallows until it was completely dissolved, or second, it could be given to anatomists for public dissection. But do not be tricked by today’s social perceptions. At the time, it was the handover to anatomists that was quite the scandal. Archives are full of convicts’ appeal letters begging to be left to dry at a crossroads rather than ending up on the dissection table of an anatomy amphitheater. Bodies were therefore available, but not in the quantities that would have been expected given the criminal codes and the royal decrees of 17th and 18th century Britain.

Medical academies were multiplying by the end of the 17th century in Europe and faced a critical shortage of human bodies. But then, this situation became another example of elementary economics: when there is a demand, the supply develops. Anatomists in need of bodies turn to an informal alternative, a literal “underground economy" that would find transport and provide cadavers to research centers outside of the formal and legal systems. The phenomenon is nothing new: the retrieving of corpses for “auctioning” had occurred before in Europe, for example, enabling people like Leonardo da Vinci to draft his impressive anatomical sketches. But in the 18th century, England moved into the pre-industrial transition, and the issue of body trading did not escape the trends of this context.

You dig, you earn

Digging up freshly buried bodies before sneaking them to the local anatomy research center became a real small business, especially since anatomy school professors and students were not the only ones interested. Surgeons, curious amateur researchers, sculptors and painters were concerned about the proper observation of the human body, for learning, or for the accurate artistic depiction of a vast array of features ranging from muscles to the face2. “Body snatching” became a lucrative business for a whole host of enthusiastic service providers who were at times described as "resurrectionists".

And as with any economic activity, the level of service varied and so did the rates. The British archives have particularly interesting documents where price lists could even be seen. For example, in 1795, in Lambeth, a group of fifteen “body snatchers” provided the Court with their rates during their trial: two guineas and a crown per corpse. This was at a time when a textile worker earned one guinea a week. In 1828, due to inflation, the physician Astley Cooper, a leading specialist in vascular surgery, estimated the average price per body at eight guineas, although he specified that the price could vary from one to twenty.

The main criterion was obviously freshness, but many variables came into account. Gender, age, and competition conditions of the body trade at a specific situation. A man's body was more expensive: their muscles, which were generally more developed than those of women, were easier to dissect and study. Sales exploded in the winter, a season when the bodies were well preserved by the cold temperatures. And sales and prices went down in the summer, when temperatures accelerated the “sell-by” date of a body.

It was quite a profitable activity. Body snatchers could easily retrieve six or eight bodies in one night and the initial investment was quite modest: a shovel, a lantern, a large bag, and a wheelbarrow for the most part. Knowing when and where to dig was no trouble. All that was needed was to watch over the burials, slip a coin to the gravedigger or sacristan, make a few small deals with the registrars or the hospice nurses, and all the information was gathered of where to dig next. Most expeditions were made at night, preferably avoiding full moon nights. With training and experience, diggers could reach a coffin within thirty minutes.

In London alone, historian Ruth Richardson estimates that 200 people were practicing "body snatching" by the 1830s. For decades, these people provided the hospitals of every major city in the country, from London to Edinburgh with several thousands of bodies a year.

A legal grave

One of the strengths of the profession was that the penalties incurred were relatively minor, for two reasons. The first is the collection of evidence. In order to punish a body snatcher, the bodies needed to be found, not an easy feat when these bodies were precisely provided for a quick dissection, that would be followed with several rounds of use by researchers and then a cutting and distribution of body parts across students, all in a relatively quick period of time. The second was legal. Taking a body out of a cemetery was an action placed within a legal limbo. Once a person died, and the body was buried, there was no person and the body did not belong to anyone. The extraction of a body could not classify as a misdemeanor, a theft, or a crime. All that could be prosecuted by judges was the desecration of a grave or, in some cases, violence committed between rival gangs fighting for the snatching business.

Such fights extended at times even into the hospitals themselves. The London-based Borough Gang of “resurrectionists” was active until 1825 and led by Ben Crouch, a former porter at the Guy’s Hospital3. In one episode, the gang arrived in 1816 into the autopsy rooms of Saint Thomas' Hospital School to slap physicians and ransack the corpses sold by their competitors, in order to make the statement that they were expected to be “exclusive” suppliers and demanded a “loyal” clientele. On the rare occasions when they were caught, the body snatchers would get a few lashes or a conviction for indecency, but in practice the police tended to turn a blind eye.

But some episodes that have remained popular through the centuries have not been fully understood in the context of the body trade. The story of the murders of some 16 individuals by serial-killers William Burke and William Hare, is well known. The two men were indeed convicted for murder, but less known is the fact that they sold the corpses to the University of Edinburgh. Out of laziness towards digging up bodies, the two accomplices had found a simple solution to make the body supply chain more “efficient”: they simply suffocated the guests staying at their inn4. A further curious detail of this case was that Robert Knox, the anatomist who had bought the bodies, got away without the least judicial concern.

Fasten your corpse for the afterlife

Being England a nation of inventors and entrepreneurs, one of the amusing effects of the body trafficking economy was the development of another business: body securitization. The horror sparked in the public by the rise of body snatching led many clever people to imagine and market plenty of tricks and gadgets intended to complicate the lives of resurrectionists: guard services, reinforced funeral slabs, triple-locked vaults for the wealthy, and even, coffin cages, a design with metal hoops that protected the recently buried. Newspapers at the time were full of advertisements or announcements for these innovations, which were sometimes outright creepy: some funeral services proposed to firmly attach the remains of the deceased to their coffins to make body snatching more complicated.

The trade is killed in the act

In 1832, in the face of widespread disapproval, the British parliament intervened in the body trafficking economy. The Anatomy Act allowed physicians to use the remains of poor people whose bodies have not been claimed by family or friends, literally killing the snatch market. Given the general misery and pauperous standards of living in London's working-class neighbourhoods, human bodies become much easier to find in the capital's hospices and mortuaries.

The law was met with general hostility. Many English citizens protested a law that reproduced social inequalities even after death. The sentiment of some was that abandoning the bodies of the miserable to the scalpel could be also juxtaposed to the fact that only the rich could afford a burial worthy of their name. Such a scandal in a society that was for the most part religious and believing in the resurrection of the body did little to prevent the law from being passed by parliament. In the aftermath, there was a drastic drop in the price of human parts in the black market. Body snatchers had to quickly turn to other trades.

Nevertheless, the impact of body snatching and the black market of human parts had its imprint on society, and was in turn reflected by cultural production directly or indirectly. Such is the case of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818): it is through the procuring of body parts from different providers that her hero gives life to a composite creature. Even in the 20th century, we see the figure of the mad scientist reduced to digging up the corpses necessary for his experiments, such as in H.P. Lovecraft’s novel Herbert West, Reanimator5 which in turn inspired the film Re-Animator (1985), by the late director Stuart Gordon.

Notes:

1. Author Note: Try to take a serious look under the rib cage of a body who's just been hit fifteen or twenty times with an iron bar through the gourd. It is quite a uphill struggle to learn anatomy with such damage.

2. Author Note: At the time of painting “The Raft of the Medusa", Theodore Gericault was regularly wandering around Paris with pieces of human bodies smuggled out of the Beaujon Hospital. Hence the beautiful green and yellow reflections of his corpses.

3. Translator Note: Inglis, Lucy, Georgian London: Into the Streets, Penguin Books, 2013.

4. Author Note: Only Burke was hanged in front of 25,000 people on January 28, 1829. Before being dissected himself by the honorable anatomist Alexander Monro. Karma.

5. Author Note: It should be noted how Lovecraft's racism is fully expressed in this narrative: Dr. West concludes that he gets nowhere in his experiments because of the "bad quality" of the bodies he is provided with, that is, those of blacks or italians.