Medical History: The “K” Syndrome

A highly contagious disease breaks out in Italy and threatens to contaminate the whole of Europe. Sick people remain in isolation. Caregivers risk their lives to protect them in a world in crisis. This disease had nothing to do with the medical field.

A look back at a highly contagious disease, that never was

A highly contagious disease breaks out in Italy and threatens to contaminate the whole of Europe. Sick people remain in isolation. Caregivers risk their lives to protect them in a world in crisis. Though resembling the current COVID-19 pandemic, this disease had nothing to do with the medical field.

Made by our partners in esanum.fr

Tiber Island (Italian: Isola Tiberina) has been at the heart of Roman history since the first inhabitants of the area chose it as the heart of the “urbs Roma”. It was a logical choice: it is much easier to build two small bridges on either side of the island than to bother building a longer one elsewhere.

In the 2020 context, it is interesting to note that the island has occasionally been associated with epidemics. In the 3rd century B.C. and while a plague ravaged the Roman streets, Tiber Island was chosen as the site to build a temple to Esculape, the Roman equivalent of the Greek god of medicine Asclepius. The tradition survived the empire and the island continued to serve as a medical sanctuary over the centuries. In 1585, the Hospitaller Order of the Brothers of Saint John of God (a Catholic order), chose to settle here again to found the Fate Bene Fratelli Hospital (in Italian: Ospedale San Giovanni Calibita Fatebenefratelli).1

For several centuries the medical monks settled there, followed a mission they had set for themselves: to alleviate the suffering of their contemporaries, with a focus on looking after the victims of the great epidemics. This became in itself a strong specialty of the caretakers at the Ospedale Fatebenefratelli. And they continued with this mission until the middle of the Second World War when their raison d'être took an unexpected turn.

Rome, Autumn 1943

The hospital, which was extensively modernized in the early 1930s, was then run by Giovanni Borromeo, a renowned medical professor who had always kept his distance from the Fascist party. Without really succumbing to Italian resistance, he nonetheless refused two professional proposals that were certainly attractive, but conditional on his joining Mussolini's party. The professor preferred to join the hospital on the Tiber island. That hospital did not pose such conditions, as being a religious establishment, the Ospedale Fatebenefratelli belonged to the Spanish order of the Hospitaller Brothers. Until 1943, Borromeo continued his work in an uneventful, and routinely manner as much as possible, even amidst the world war, helped by the quasi-extraterritorial status enjoyed by his establishment.

In September 1943, everything changed: the Allied advance in southern Italy provokes German intervention. The Wehrmacht occupies northern Italy, including Rome, and administers it almost directly. Mussolini, as the puppet leader of the Republic of Salo, no longer had much control in an Italy cut in two. In Rome, it was SS officer Herbert Kappler2 who actually controlled the city, under the more distant military authority of General Albert Kesselring.

For Italian Jews, this was a catastrophe: although they had until then enjoyed relative tranquillity despite the Fascist anti-Semitic laws of 1938, they are now under the sight of one of the most fervent supporters of the Final Solution. In Belgium, Kesselring’s previous post, he had already ordered a series of round-ups and organized the first convoys to the concentration camps. In September 1943 he embarked on an identical policy in Rome. After having confined the Italian Jewish community, largely concentrated in the Ghetto of Rome, by October 15th he ordered the round-up of 1,259 Jews, most of whom were sent to Auschwitz. 16 of them returned.

A mysterious disease

In this treacherous context, the Ospedale Fatebenefratelli continued to operate as usual. The hospital was just a stone's throw from the Ghetto district from which it is only separated by the Ponte Fabricio, a bridge. But during that time, Prof. Giovanni Borromeo's teams had plenty of worries of their own: since October 16th, their services have been receiving a flow of severely affected patients. But the physicians were unable to make a precise diagnosis of particularly serious symptoms that included cramps, convulsions, tetany, dementia, or paralysis. The most affected patients died after slow and unbearable asphyxia that was reminiscent of that in tuberculosis patients. The provisional name Prof. Borromeo gives to the unknown disease he faces, the syndrome K, is a direct reference to the bacillus Koch (Mycobacterium tuberculosis), the tiny bacterium responsible for tuberculosis.

Hidden away in two large rooms hermetically sealed off from the outside world, one for women and children and the other for men, the syndrome is all the more frightening because it is highly contagious. Barely sixty meters wide, separated from the rest of the Italian capital by two tiny bridges, the entire Tiber island is now a pressure cooker, a biological time bomb from which the epidemic can escape at any moment. This is how Prof. Borromeo calmly explains to the SS officers who have come to demand explanations of what became now a legendary act of kindness.

Being informed of the biological threat at hand the SS officers, accompanied by one of their own physicians, choose to retreat given the prospects of catching the unknown disease themselves. The mere option of crossing the large, hermetically sealed doors so that the SS officers could take a look for themselves is out of the question. From their standpoint, they could already hear the clear hiss of profound coughs. At that moment, the champions of the Nazi military elite were elegantly fooled. The K disease did not exist.

A swift plan

This was obviously impossible to set up without the complicity of most of the medical staff. This was, in itself, the most humanistic medical scam of the Second World War. It was born quickly, on the night of October 15th to 16th, when Jewish survivors of the round-up ordered by Kappler desperately searched for a way to escape from the German soldiers.

Some had the idea of turning to one of the hospital physicians, Dr. Vittorio Emanuele Sacerdoti. A Jew himself, he had long since been authorized by the hospital management to work under a false identity. Dr. Sacerdoti discussed the matter with Prof. Borromeo, who did not hesitate - and the magnificent fiction of the deadly and mysterious epidemic, born that night, immediately took shape.

On October 16th and the days that followed, Borromeo and the hospital staff welcomed several dozen Jewish compatriots as patients. Many of them had indeed some signs of a cold, and the plan was to let them recover “in seclusion”, as the head physician and his colleagues worked intensely to draw up a list of symptoms, each one more frightening than the other, in order to divert Nazi suspicion. "The Nazis ran away like rabbits," laughed Dr. Sacerdoti in a 2004 interview he gave to the BBC.

A medical guerilla

Once the plan was set in motion, it was hard to stop it. While the K syndrome continued to keep the Nazi troops at bay, the entire Ospedale Fatebenefratelli continued its gradual transformation into an urban medical guerilla site. A radio was soon installed in its basement to make contact with the Republican partisans and the Allied command, which was gradually chipping away the Nazi-controlled Italian territory through intense fighting.

More and more "sick people" were admitted to the hospital among the real patients, under the noses of German authorities. Italian Jews, political opponents, it did not matter: The administrative documents contained the words "Syndrome K". The same logic was used on forged death certificates signed when a way would be found to smuggle the refugees into safety. As they escaped, their “bodies” would all indicate the same cause of death: "morbo di K", the K syndrome.

The coining of such a term is also owed slightly to the mind of another of the physicians involved in this rescue operation, the physician and anti-fascist activist Adriano Ossicini. "When the K syndrome appeared on a patient's records, it indicated that the sick person was not sick at all, but that he or she was Jewish. For us at the hospital, the “K syndrome” was our way of signaling 'I admit a Jew', as if they were sick when we knew that they were all healthy," explained Dr. Ossicini in a 2016 interview, at the age of 96.

How many false patients were saved this way? As time went by, it was impossible to know precise figures, but the Australian Holocaust historian Paul R. Bartrop estimates that some 100 people were saved between October 1943 and the liberation of Rome in early June 1944. A hundred lives were saved by an improvised plan set up within a few hours by a handful of physicians and clerics3 who did not stand frozen in the face of brutality.

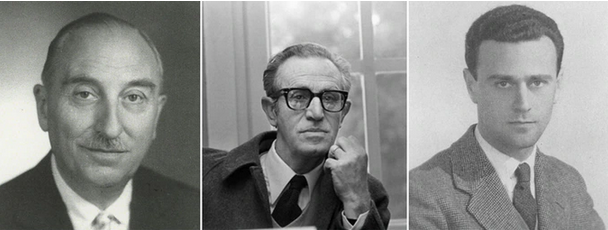

Left to right: physicians Boromeo, Ossicini and Sacerdoti

Giovanni Borromeo, who died in 1961, was recognized as "The Righteous Among the Nations" in 2004 by the Yad Vashem memorial, which, among other things, honors the memory of those non-Jews who helped save Jewish lives during the Second World War. In June 2016, the Ospedale Fatebenefratelli as such was honored by the American Raoul Wallenberg Foundation, which pays tribute to the heroic deeds performed during the Second World War.

Author notes:

1. “Fate bene fratelli” literally means "do good, my brothers".

2. For example, the massacre in the Ardéatine Pits, where 335 civilians shot in reprisal for an action by the Italian resistance was done under Kappler’s command.

3. Together with the names of Borromeo, Ossicini, and Sacerdoti, further recognition must be given to the religious superior of the hospital community, the Polish friar Maurizio Bialek, himself involved in the anti-fascist movements at the time. Without these men and without the support of their teams, nothing would have been possible.