- Pasqualetto A. Carlotta Rossignoli, modella e medico a 23 anni: «Il segreto? Non perdo mai tempo». Corriere della Sera. 30/10/2022 Medscape “Death by 1000 Cuts” Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2021 https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2021-lifestyle-burnout-6013456#1

- Schernhammer ES, Colditz GA. Suicide rates among physicians: a quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis). Am J Psychiatry. 2004 Dec;161(12):2295-302. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2295. PMID: 15569903.

- Gold KJ, Sen A, Schwenk TL. Details on suicide among US physicians: data from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013 Jan-Feb;35(1):45-9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.08.005. Epub 2012 Nov 2. PMID: 23123101; PMCID: PMC3549025.

- Dutheil F, Aubert C, Pereira B, Dambrun M, Moustafa F, Mermillod M, Baker JS, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Navel V. Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019 Dec 12;14(12):e0226361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226361. PMID: 31830138; PMCID: PMC6907772.

- Seo C, Di Carlo C, Dong SX, Fournier K, Haykal KA. Risk factors for suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among medical students: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021 Dec 22;16(12):e0261785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261785. PMID: 34936691; PMCID: PMC8694469.

- Tsegay L, Abraha M, Ayano G. The Global Prevalence of Suicidal Attempt among Medical Students: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatr Q. 2020 Dec;91(4):1089-1101. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09805-7. PMID: 32789601.

- Blacker CJ, Lewis CP, Swintak CC, Bostwick JM, Rackley SJ. Medical Student Suicide Rates: A Systematic Review of the Historical and International Literature. Acad Med. 2019 Feb;94(2):274-280. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002430. PMID: 30157089.

- Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, Sen S, Mata DA. Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA. 2016 Dec 6;316(21):2214-2236. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17324. PMID: 27923088; PMCID: PMC5613659.

- Tarchi L, Moretti M, Osculati AMM, Politi P, Damiani S. The Hippocratic Risk: Epidemiology of Suicide in a Sample of Medical Undergraduates. Psychiatr Q. 2021 Jun;92(2):715-720. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09844-0. Epub 2020 Sep 7. PMID: 32895751; PMCID: PMC8110500.

- Duò. Pavia, studente 30enne di medicina si suicida/Temeva di perdere borsa di studio. ilsussidiario.net. 27/07/2022

We all want to be Carlotta

The name of Dr Carlotta Rossignoli has been frequent in Italian news and social media recently. Her story sparks a wider analysis on Medicine and Surgery studies.

Translated from the original Italian version

An honours degree and much controversy

For several weeks, the story of Carlotta Rossignoli, who, at only 23 years of age, graduated in Medicine and Surgery with top marks from the Vita-Salute San Raffaele University in Milan (a private university), has been the talk of Italy. The degree obtained by Dr. Rossignoli six months earlier than expected caused a sensation. In particular, the media narrative with which Carlotta's story was told caused a stir. A narrative that placed great emphasis on two concepts: time, which must always be optimised, and performance, which must always be maximised1.

I don't want to talk about the newly appointed Dr Rossignoli or make any kind of analysis of the history that strictly concerns her. She graduated top of her class, and I wish her the best in her career. I hope she can share her skills and make an important contribution to improving the health of patients.

Dr Rossignoli on her graduation day (credit: Instagram)

I can't, I have to study

So what am I going to talk about? I would like to start with Dr. Rossignoli's story to talk about some of the dynamics that characterise the Medicine degree course in Italy today.

For Italian medical students, or for those who are doctors today and have studied medicine in Italy, what almost certainly struck most about Rossignoli's story was not the fact that she graduated early, but that she seems to have managed to retain so many interests and passions during her years at university. Those who know the degree course in Medicine and Surgery are well aware of the workload that characterises it, the competitive and individualistic environment, the renunciations that one is forced to make as the years go by because medicine swallows up interests and passions more and more every day.

The articles that told Carlotta Rossignoli's story portrayed a person who, by organising herself and wasting no time, managed to graduate with top marks, before the others, without giving up sport, modelling and television presenting, or travelling. I do not know how Carlotta's studies, or the life context in which they took place, I only have a partial vision given by the narrative of the press and social media (including her own social media). Assuming that everything represents the true, unfiltered reality, I do not hide my astonishment.

I know of medical students who give up competitive sport in order to be able to maintain the pace required for study. I know of those who, having to work even part-time to pay for their studies, inevitably fall behind in their exams. I know of thousands of students who manage to carve out just a few days of holiday a year, fitting everything into exam dates.

Let me be clear: I am not here to make inferences about Carlotta Rossignoli's course of study. I am simply here to wonder why I am so surprised if a medical student, in addition to studying, cultivates some passion or perhaps manages to find a way to do a job that allows them to weigh less on their family.

'Your youth ends today'

Many doctors who studied at a major Italian university were greeted with these words on their first day of class: 'Your youth ends today'. The corollary of this peremptory sentence was more or less this: 'From today onwards, any other interests will take a back seat, you will stop going out at night, you will stop having time for friends and girlfriends. You will not be able to engage in anything that takes up your time. From today you will be hunched over books, and when you are not hunched over books, you will be in class, and when you are not in class, you will be in hospital. This is what awaits you for the next six years".

The idea that medical school should be all-consuming and alienating is common, so common that students themselves exorcise the issue with memes to share on the web. The question I ask myself is whether this way of approaching the study of medicine really leads to better, more prepared, more capable doctors, or whether it is a self-referential mode for its own sake.

I do not want to praise mediocrity. I am convinced that a good university preparation is essential to become good doctors. And I am convinced that this must cost effort and commitment. However, I wonder whether stress and despondency have anything to do with good preparation. I wonder if this mode, which nails thousands of medical students to their desks, reserving only crumbs for clinical and practical work, is actually the best from a methodological point of view. I wonder whether building a highly competitive and individualistic environment is really what is needed to develop the best skills of tomorrow's doctors.

The primary goal of almost all medical students today is to maintain a high average, because that is what the system in which they are placed requires. There are departments that one cannot enter to do internships if the average is low, there are dissertations that one cannot apply for if the average is low, there are specialty schools where a 0.25 gap makes a difference.

What should one do to keep the average high? Of course, pass exams with high grades. And how does one achieve this? By swallowing avalanches of notions. Medical students are engaged for years in a constant mnemonic effort, to remember the course of every artery, to remember the chemical formula of cholesterol, to remember the coagulation cascade, the various diseases of rheumatology (which by the fourth year seem to differ only in name).

From the very first year of university, a mountain of notions are memorised that seem more functional to passing the exam than to building a doctor's basic cultural background. It is a constant race to study the outdated classification, to spend an extra hour on the ward, to stand out from the others.

In the world of ultra-specialised medicine, perhaps a school that teaches everyone, as best it can, to always keep an overview, to never lose sight of the patient in their complexity, physical and psychological, would be more useful; a school that develops diagnostic and clinical skills. A school that teaches how to organise and manage a team, because the doctor who treats diseases armed only with his leather bag is a relic of the past. Teamwork is the basis of modern medicine, and this too should perhaps be taught.

I wonder whether a less competitive environment, less focused on booklet grades, whether a school that is less all-encompassing and more congenial to the development of individual potential and the aptitude for teamwork, could make the life of medical students less pressurising and alienating. Not less tiring, because studying medicine entails effort, but more motivating and useful for the profession one is going to pursue.

The youth of medical students should not end on the first day of class in my opinion, but be accompanied by the university towards a maturity richer in awareness and skills.

The Hippocratic syndrome

In the current situation, in many cases one studies in function of the exam grade, not in function of learning. In most cases we go to the department to acquire training credits, not to learn the profession. We attend a seminar, a course, an activity, not to increase our knowledge, but to accumulate points and have that 0.5 that can make life more like the ideal that is in our heads or that we believe is in the head of others.

Now, it is easy to imagine what impact the natural setbacks that can occur in a years-long academic career can have. A failed exam, a grade that is not deemed to be in line with the roadmap one has set oneself or the reputation one wants to present to others, an artery that one fails to pierce for blood gas in front of impatient tutors and know-it-all colleagues, can send young medical students into crisis.

In recent years, several analyses have been conducted on the mental health status of doctors, which have shown a greater likelihood of suffering from anxiety disorders and depression, as well as a greater propensity to commit suicide than other professional groups2-4.

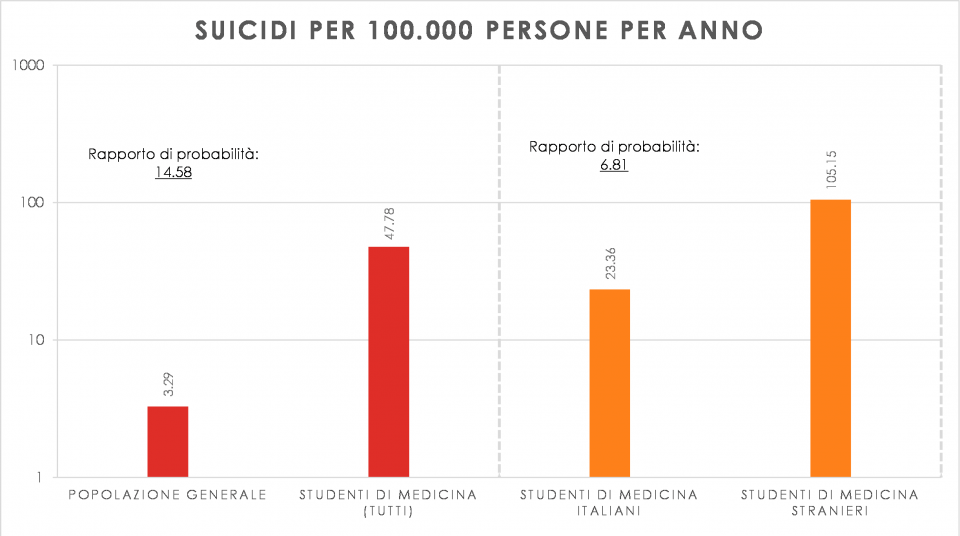

The situation for medical students does not seem to be any different, although there is not much data available in the literature5-8. In a recent study9 conducted by a group of Italian researchers, one speaks of the Hippocrates Syndrome. In the analysis, it is not only highlighted that doctors have higher suicide rates than the general population, but also that medical students, compared to the general population and other university students, represent the category most at risk of suicide.

Chronicled events, even recent ones10, do not therefore appear to be isolated cases, but a symptom of a problem. A problem that, however, does not seem to interest either the universities or mainstream communication.

Comparative data of suicide cases per 100k people/year, betwen general population and medical students, and comparative discrimination between italian and foreign medical students. Data from research by Tarchi et al.9

A different approach to the study of medicine

I am aware that I sketch here only predominant reflections on medical school situations that sometimes may seem toxic for those who attend it, but I believe that the topic deserves some serious investigation. It is not just an Italian problem; extensive and shared research must be conducted to fully understand the causes of the phenomenon.

I don't know whether the years Carlotta Rossignoli spent in Medicine were actually so serene and full of other extra-curricular activities and hobbies, as it appears, but that's not the point. The point is that I think we should start thinking that the life of medical students, all of them, should be serene.

Medical schools should take the well-being and mental health of their students seriously and start collecting data on the current situation and sharing these findings. In a major Italian university there have been five medical students who have died in the last five years.

I believe that universities should question themselves on the setting of this degree course, which often gives little space to reasoned and professionalised learning, to the construction of a multidisciplinary thought pattern that nurtures the sharing of knowledge and experience. I believe it is incumbent on medical schools to make a firm commitment to accompany every student, leaving no one behind. This, in my opinion, would be the most important record to set.