Masturbation: When medicine had a heavy hand (Part 1)

When Atum spread his divine seed over Egypt, could he have guessed that from the 18th century onwards masturbation would agitate the medical world so much?

In our Medical History series, journalist Jean-Christophe Piot recounts some of the most significant pages in the history of medicine using historical facts and story-telling.

When Atum, the sun god creator, spread his divine seed over the lands of Egypt, could he have guessed that from the 18th century onwards masturbation would agitate the medical world so much? Although the physicians of Antiquity did not care about masturbation, or even found some virtues in it, attitudes about it became tense in the 15th century and turned sour during the 1700s.

Article translated from the original French version

You can visit Part 2 of this story here

"Mother of all vices", "cause of all evils", "disastrous habit" and so on: 19th century literature rivals each other in the use of more inventive periphrases to describe good old masturbation. The excesses of this general disapproval may make us smile today. But the moral, religious and medical condemnation of this practice, after having emerged in the modern era, took a radical turn in the 19th century. The consequences for some "patients" - especially young girls - were extremely severe. How on earth did it come to this?

When mythologies set out to describe how the world came into being, they produce more or less colourful tales ranging from Yahweh's heavy weekly workload to stories of primordial eggs, giant skulls and trees of life. The Egyptians don't go into detail: in the beginning was the wank. But literally: it is by allowing himself a little solitary pleasure after having emerged from the original Ocean (the Nu and Naunet) that the god Atum creates his own descendants, born from the divine sperm spread over the first lands of Egypt. These twins, Shu and Tefnut, will in turn beget a good part of the (very) rich Egyptian Pantheon, in a more classical way.

While Egyptian mythology gives it a central place, other pagan religions make little reference to masturbation. The practice does not seem to be advocated or particularly taboo, but rather absent from narratives where sex is central, at least in the Greco-Roman world. And even in Olympus, there is nothing obvious: we only learn from a work by Dio Chrysostom that the Great Pan is said to have introduced his father Apollo to the joys of self-stimulation, before touring all the mountain pastures in the area to spread the word to the shepherds, who must have found their evenings quite long up to then.

But if we descend from divine altitudes, what do the physicians of antiquity say? Well, nothing or almost nothing, with rare exceptions. Hippocrates only mentions the subject in rare allusions, and if Galen quickly mentions Diogenes the Cynic, reputed to have relieved himself in the middle of the agora, it is by interpreting this as a stopgap, as the need for the philosopher to get rid of an imbalance of humours.

Galen is more precise about female masturbation, which he describes as a necessary treatment: "[women] are more restricted in their use of coitus to rid themselves of their acrid humours; widows, wives whose husbands are absent, girls after puberty and before marriage do not have the possibilities that are available to men and boys in similar circumstances". Hence various "warming treatments" to induce in the patient "convulsions accompanied at the same time by pain and pleasure, followed by the emission of a cloudy and abundant semen. She will then be free of all the pain she has felt". In short, for Galen, masturbation is a good way to cure the consequences of a bad elimination of humours, due to the absence of a purifying coitus.

The boy Onan

How did we come to the moral, religious and medical condemnation of masturbation that subsequently characterised the West? Partly because of a major misunderstanding, born of a minimally questionable interpretation of a famous episode in the Jewish and Christian narratives: the sad fate of the brave Onan. In the Torah, as in the Old Testament, the poor boy is ordered by his father to take the place of his dead brother in his sister-in-law's bed, in order to ensure the family's descent. But Onan does not see it that way: "But Onan knew that the child would not be his; so whenever he slept with his brother’s wife, he spilled his semen on the ground to keep from providing offspring for his brother. What he did was wicked in the Lord’s sight; so the Lord put him to death also.”

On closer examination, this famous text - Onan gave us the word onanism - has no direct connection with masturbation, for two reasons. Firstly, because there is no indication that it is about masturbation: the text could just as well describe the contraceptive practice of withdrawal. Secondly, because the sin that makes God angry is not so much masturbation as the refusal of a Jewish law: not to provide offspring for one's brother is a crime. Christian tradition takes up the Hebrew episode and from Saint Augustine to the Council of Trent, exegesis begins to consider that by condemning everything that prevents procreation, God also condemns masturbation.

Physicians, on the other hand, seemed to be above these concerns, at least from a medical point of view: still trained on the basis of the ancient corpus, they saw the practice as a means, like any other, to regulate the humours. In the 15th century, Saint Antoninus condemned physicians who prescribed remedies to provoke night-time pollution "even if it is not done for pleasure, but to help lighten nature and health".

Another Jesuit scholar, Toledo, says the same thing: masturbation "is unnatural and is not permitted either for health, or for the preservation of life, or for any other purpose. Therefore, physicians who recommend such an act for health reasons are sinning in an extremely serious manner." A few years later, another Jesuit, the Portuguese Rebellus, took up medicine outright: "The assertion that it is permissible to use the hand and rubbing to expel corrupt and harmful semen in order to preserve health must be condemned."

Medical turn, moral turn and anti-masturbation manual

As believers themselves, physicians are under pressure even if they do not all share the Church's judgement, starting with Fallope who even grants male masturbation some... let's say unsuspected virtues. For the anatomist "a good method of strengthening the penis of young boys, in order to make them better able afterwards to procreate, is to pull on the penis, vigorously and repeatedly, in order to make it longer" (De Decoratione, 1600).

Almost paradoxically, it was scientific progress that paved the way for an even more catastrophic view of solo groping. The revival of medical research and the gradual abandonment of old Galen's theories led to a gradual rejection of the theory of humours, which in the process undermined the main argument that practitioners had put up against the Church: the need to evacuate corrupted humours. Not only was masturbation no longer good for your health, but in fact the opposite was true, according to the medical theory that gradually became established during the Enlightenment and then in the 19th century.

Obviously, the evolution did not happen in the blink of an eye, but a short pamphlet contributed greatly to spreading a real moral panic in public opinion, with all the more success as it benefited from the progress of printing and publishing.

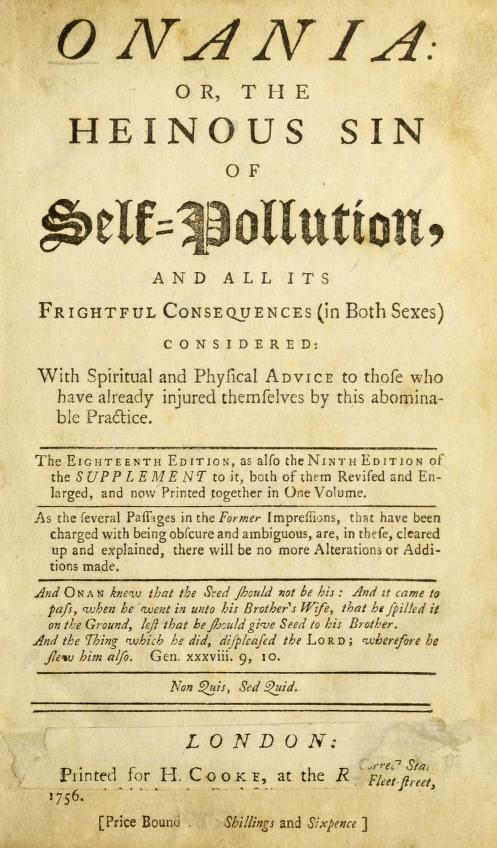

In 1715, a small anonymous work, Onania, was published in London, whose subtitle was already a poem: "Or the odious sin of masturbation, and all its dreadful consequences for both sexes, with moral and physical advice to those who have already caused harm to themselves by this abominable practice". One more anti-masturbation manual - the genre already had its little success - but which was to become a staggering bestseller for its time.

Translated, completed and extended, Onania was reprinted 22 times in 60 years. A copy was even found in the library of Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States. These successive editions, accompanied by "letters from readers" of increasingly dubious authenticity, extolled the merits of a "fortifying tincture" and a "prolific powder"; these two remedies supposedly to calm ardour were available from... the publisher. Long attributed to a mysterious Dr. Bekkers, the book was in fact the work of John Marten, a self-taught surgeon and medical huckster who had previously been imprisoned for writing a book on venereal diseases that was considered obscene and fanciful.

1756, 18th edition. We never get tired of it.

The fact remains that, in substance, the attack is twofold. According to the author, masturbation is both a religious and a medical disaster. Religious first: "For fornication and even adultery, although they are odious sins, one can plead human frailty and the inclination of nature. But masturbation is a sin that perverts and destroys nature. He who is guilty of it works for the destruction of his species, and in a certain way strikes a blow at Creation itself." And that is no small thing.

From a more down-to-earth perspective, onanism is also described as a medical abomination. For the first time, "reading with one hand only" became the mother of all diseases. Gonorrhoea and impotence, two great classics, are obviously on the list. But everything is included, with the same conviction as for the lung of Molière's "Le Malade imaginaire". Ulcers? Masturbation. Convulsions? Masturbation! Epilepsy, consumption? Masturbation, I tell you! "Many young men who were robust and well built before indulging in this vice, found themselves exhausted and, masturbation depriving their body of its vital and restorative moisture, became dry and emaciated, and were led to the grave."

The Swiss support

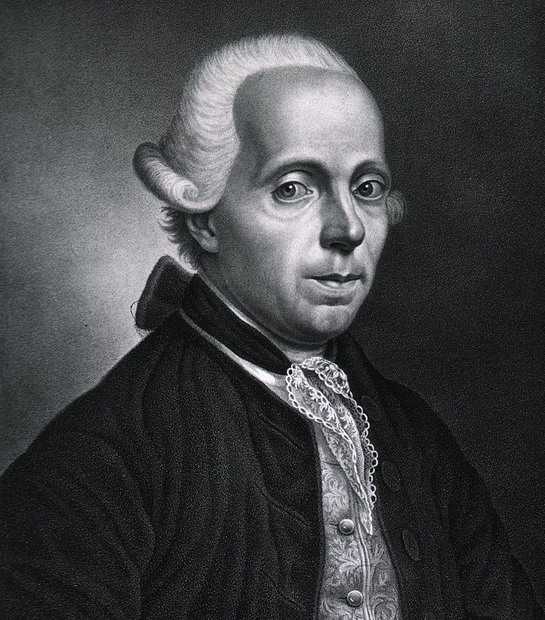

The publication in 1760 of a text written this time by an eminently famous physician was to deepen the furrow. Samuel Tissot, a Swiss friend of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, wrote the leading medical work on the subject, from which he was to gain a little fame in Europe. L'Onanisme: essai sur les maladies produites par la masturbation (Masturbation: Essay on diseases created by masturbation) will mark scientific thought for a good century and a half. Reissued 63 times - and well into the 20th century - this classic work brings the credit of a leading scientist to the previous Onania work; Tissot is closely associated with the Enlightenment and, moreover, becomes the official physician of some crowned heads.

For Tissot, masturbation is a pathology. Worse still, it is a deadly pathology for the mind and body - one only has to look at the slightly caricatural clinical picture he paints of his patients ravaged by the "disease":

"The painting of danger (...) is perhaps the most powerful motive for correction, it is a frightening picture capable of making one recoil in horror (...) the patients become stupid and so stiff that I have never seen such a great immobility of body. The eyes themselves are so dazed that they no longer have the capacity to see (...) Here are the main features: a general decay of the machine; the weakening of all the bodily senses and all the faculties of the soul; the loss of imagination and memory; imbecility, contempt, shame; all functions disturbed, suspended, painful; long, strange, disgusting illnesses; acute and ever-recurring pains; all the evils of old age in the age of strength (...) disgust for all honest pleasures, boredom, aversion to others and to oneself; horror of life ... anguish worse than pain; remorse worse than anguish..."

Put your hands away, Uncle Samuel is watching you.

Ridiculous? And yet... by the end of the 18th century, this apocalyptic vision had taken hold throughout Europe. And the worst is yet to come. While Tissot advocated natural remedies - camphor and the like - as an antidote to masturbatory impulses and simply advised getting out of bed as soon as you woke up, the very positivist 19th century was much more radical. It will deploy everything to fight against what it considers a moral vice, a pandemic perversion that many believe can ruin the whole society.

Literally everything.

So then, just for fun, and because it's still good news...

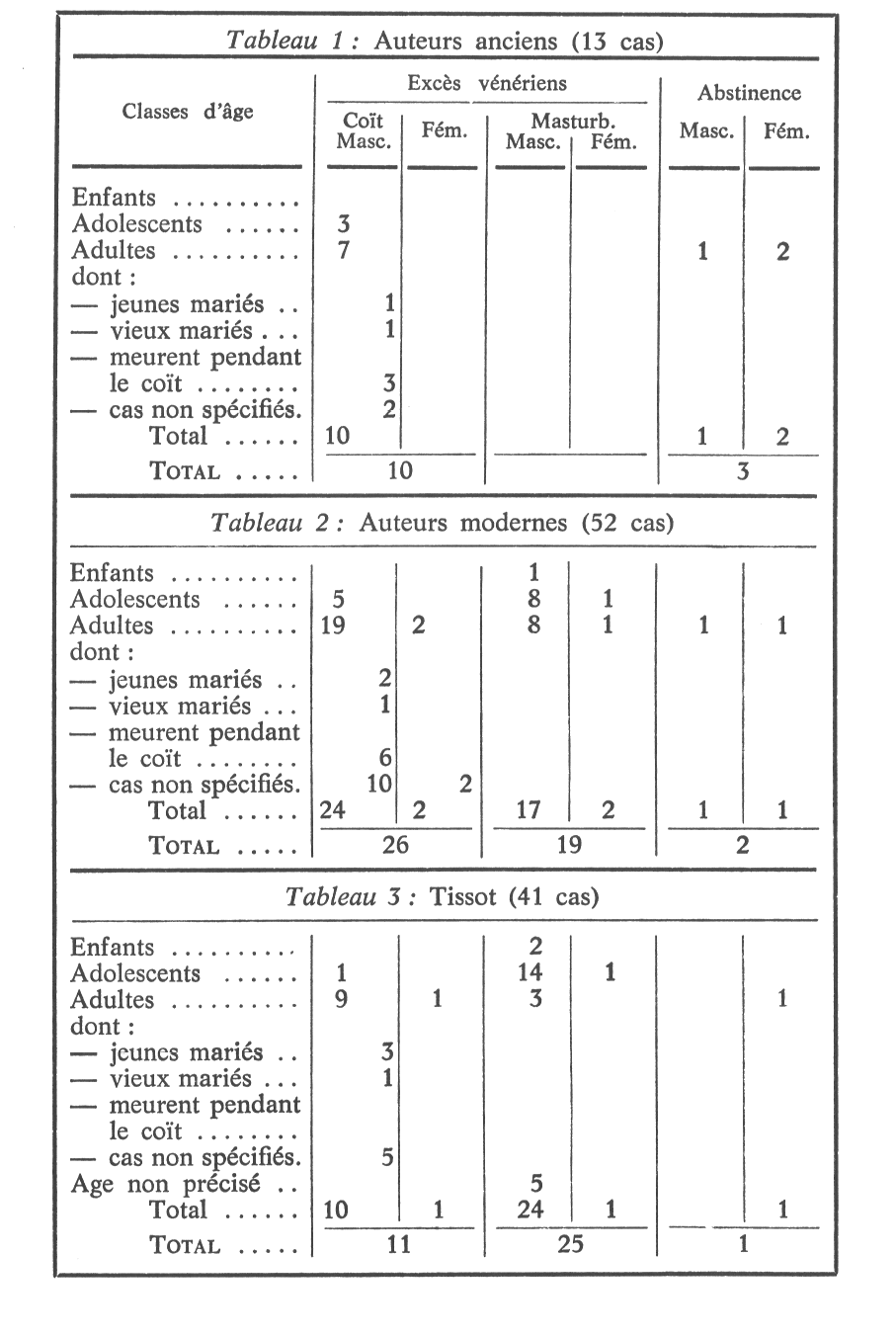

...in his study, Tissot reports no cases of death during coitus (unlike his predecessors):