- WHO - WHO Director-General awards Henrietta Lacks posthumously (2021)

- Mac Gill University - "Immortality in the Lab: How One Woman's Cells Changed Medicine and Ethics", by Jonathan Jarry (2022)

Henrietta Lacks: The painful burden of immortality

The HeLa tumour cells were taken from Henrietta Lacks against her will in 1951. Their history, and contribution to medicine and science over decades is incredible.

The immortality of Henrietta Lacks

Translated from the original French version

They were called "HeLa", the tumour cells - an acronym of the first two letters of their first and last names. They helped Jonas Salk test his polio vaccine, contributed to the upsurge in virology and helped trace the effects of radiation from an atomic bomb. They also played a role in the development of drugs for HIV, haemophilia, leukaemia and Parkinson's disease. We owe them advances in in vitro fertilisation. Even today, they provide us with crucial information for gene mapping and even for the development of vaccines against the human papilloma virus or COVID-19. Henrietta Lacks' cells have even travelled into space.

A short but endless life

Henrietta Lacks was born in 1920 and grew up in Virginia. She grew tobacco in the fields her ancestors had once farmed as slaves. In 1951, a gynaecologist at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, discovered a induration the size of a nickel on her cervix. What was surprising was that a few months earlier, when Ms Lacks gave birth - to her fifth child - no abnormality was detected.

At that time, this type of cancer was treated with radium, which was filled into a tube and sewn into the cervix. On the first day of treatment, the surgeon cut two small pieces of tissue out of Henrietta Lacks without her noticing. One came from the tumour, the other from the adjacent healthy tissue. The samples were then sent to the laboratory of Dr George Gey, who wanted to achieve with human cells what others had already succeeded in doing with mouse cells in 1943: to make them grow indefinitely in the laboratory.

Six months after starting this first radium treatment, Henrietta Lacks died. In Dr Gey's laboratory, the cells of the healthy tissue survived only a few days. The tumour cells, on the other hand, grew steadily, doubling in size every twenty-four hours. It was later to be understood that this is why they are immortal, because they have been altered by multiple copies of the HPV virus.

In the laboratory, it turned out that the tumour cells were so aggressive that they took over other cells in cell cultures. The researchers thought at the time that normal cells spontaneously become cancerous; but in fact their cell cultures were contaminated with the HeLa cells.

The suffering of the Lacks family

According to the WHO, "more than 55 million tonnes of HeLa cells have been distributed worldwide, used in more than 75,000 studies". In the USA, a vial of these cells costs 861 US dollars. Lacks' family and their descendants never saw this money. In the book "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks", the writer Rebecca Skloot reports that the members of the Lacks family did not even have enough money to afford their own health care.

The family had sued an American biotechnology giant last year for manufacturing and selling products whose research basis was based on cells taken from Henrietta Lacks without her consent. Ever since it became known that scientists had taken cells from her mother against her will and marketed them behind her offspring's back, there has been deep mistrust in the Lacks family.

Henrietta's children grew up hearing cruel and absurd stories about their mother; about what the doctors had done to her, that Henrietta's clones or hybrids were walking the earth and that she lived in the impact zone of an atomic bomb. A first cousin of Henrietta's told Skloot: "No one here ever understood how she died and how this thing is still alive."

And what about ethics?

In the decades following Henrietta Lacks' death, her family's concern and also anger are fuelled by the issue of race. In 1951, Henrietta was admitted to the "coloured women's" ward. Inevitably, her family questioned the way she was treated. This distrust was heightened by the Tuskegee scandal in the 1970s. Tuskegee is the name of a clinical trial conducted without her knowledge on Black Americans under the guise of medical care to learn more about the development of untreated syphilis.

Medical research at the time was rarely concerned with ethical issues. In 1954, virologist Chester Southam claimed to a dozen cancer patients that he was testing their immune systems. In reality, he was injecting them with HeLa cells to better understand the development of their disease. Later, he repeated these injections on prisoners or gynaecological patients. A total of 600 people were told that these were cancer screening tests.

A long road has been travelled. Biomedical research is now controlled, subject to protocols and endorsed by an ethics committee. Informed consent from the patient is required for tissue donation.

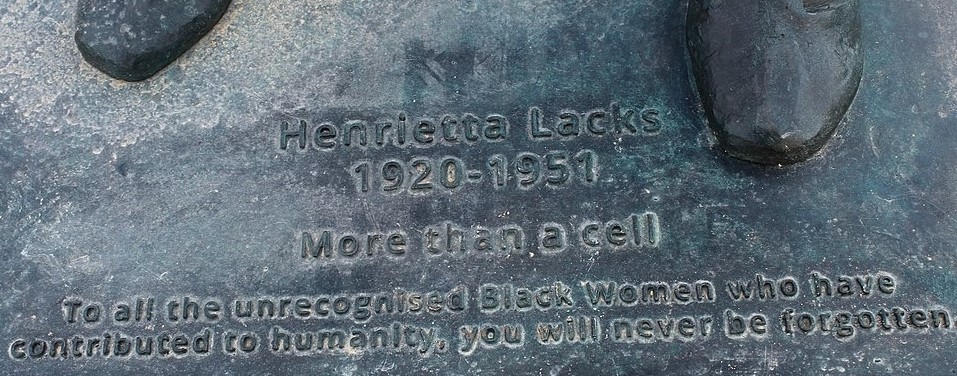

More than a cell: In memory of Henrietta Lacks

Nevertheless, in the presence of Ms Lacks' 87-year-old son, WHO 2021's director-general was keen to stress: "What happened to Henrietta was wrong.... [she] was taken advantage of. She is one of many women of color whose bodies were abused by science. She trusted the health care system to get her treatment. But the system took something away from her without her knowing it." Ghebreyesus went further and spoke openly about the Black Lives Matter movement: "We believe that in medicine and in science, the lives of People of Colour matter. Henrietta Lacks' life counted - and still counts".

"Henrietta Lacks, 1920 - 1951. More than a cell. To all the unrecognised Black Women who have contributed to humanity, you will never be forgotten."