- Akesson LS, Savarirayan R. Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva. 2020 Jun 11 [Updated 2024 May 23]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558090

- Kaplan FS, Shore EM, Pignolo RJ. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva emerges from obscurity. Trends Mol Med. 2025 Feb;31(2):106-116. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2024.08.010. Epub 2024 Sep 18. PMID: 39299836.

- Pignolo RJ, Baujat G, Brown MA, De Cunto C, Hsiao EC, Keen R, Al Mukaddam M, Le Quan Sang KH, Wilson A, Marino R, Strahs A, Kaplan FS. The natural history of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: A prospective, global 36-month study. Genet Med. 2022 Dec;24(12):2422-2433. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2022.08.013. Epub 2022 Sep 24. PMID: 36152026.

- Image note: Fred Kaplan, Mütter Museum, College of Physicians of Philadelphia - Shafritz et al., 1996

- Imag note: Alabama medicine: journal of the Medical Association of the State of Alabama 1984

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, a rare genetic disorder

FOP is a rare genetic disorder where soft tissues turn into bone, limiting movement and causing severe complications, with an average life expectancy of 40 years.

FOP: the “stone man disease”

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP), also known as “stone man disease”, is a rare autosomal dominant genetic disorder affecting the musculoskeletal and connective system. Its prevalence varies, according to publications, between 0.36 and 1.36 per million inhabitants, without any ethnic or geographical factors.

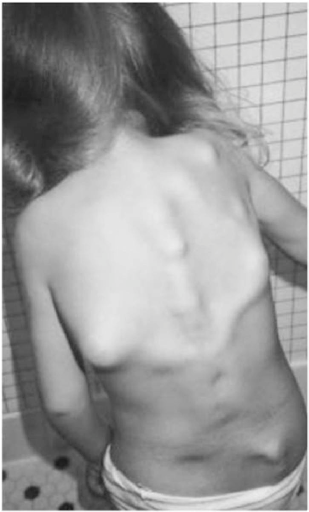

Children with FOP appear normal at birth, with the exception of congenital malformations of the big toes (hallux valgus, malformation of the first metatarsal and/or monofalangeus). During the first decade of life, sporadic episodes with painful soft tissue swellings may occur, often due to injuries, intramuscular injections, viral infections, muscle stretching, falls or fatigue. These flare-ups transform skeletal muscles, tendons, ligaments, fascia and aponeurosis into heterotopic bone, making movement impossible. Patients with atypical forms of FOP have been described, presenting the classic signs of FOP associated with an additional sign or several atypical signs (concomitant aplastic anaemia, craniopharyngioma, childhood glaucoma, growth retardation; FOP plus) or presenting significant variations in one or both of the classic signs of FOP (normal toes or severe finger shortening; FOP variants).

FOP is linked to pathogenic variants of the ACVR1 (Activin type 1 Receptor, also known as ALK2) gene, which encodes activin A type 1 receptor for various ligands, including BMP (Bone Morphogenetic Protein). The diagnosis is strongly suggested by clinical and radiological evidence, later confirmed by the molecular study carried out during a medical genetics consultation. The differential diagnosis arises with progressive bone heteroplasia, osteosarcoma, lymphoedema, soft tissue sarcoma, desmoid tumours, juvenile aggressive fibromatosis and non-hereditary heterotopic ossification.

The prognosis of POF remains unfavourable due to severe morbidity, progressive functional progressiveness and early mortality. The course is characterised by the onset of particularly disabling axial and peripheral ankylosis, with the need for assistance by one or two persons for daily activities from the beginning of the third decade.

The main complications are cardiopulmonary (repetitive pneumopathy, right heart failure, restrictive respiratory failure), neurological (headaches, neuropathic pain, allodynia, myoclonus), renal (lithiasis), cardiac (conduction disorders), craniofacial and otorhinolaryngological (TMJ dysfunction, swallowing disorders, deafness).

Advanced bony manifestations of FOP in a 39-year-old man (photocredit: Fred Kaplan, Mütter Museum, College of Physicians of Philadephia - Shafritz et al., 1996)4

There is currently no definitive treatment. The application of high-dose corticosteroids for 4 days, starting within the first 24 hours after the flare-up, can reduce the acute inflammation and tissue oedema observed in the early stages of the disease. Prevention is based on the implementation of interventions aimed at reducing falls (improved home safety, use of a protective helmet), preventing respiratory decline (incentive spirometry) and viral infections. The average life expectancy is about 40 years.

The natural history of FOP: a prospective, global 36-month study

In 2022 a global natural history study of FOP carried out by Ipsen showed the debilitating impact of the disease over the patient's lifetime. This prospective, international study followed 114 individuals with classic FOP (ACVR1R206H mutation) over 36 months to assess disease progression under standard care conditions.

Key clinical findings

- Flare-ups and HO development: 71.9% of participants experienced flare-ups, predominantly in the upper back (17.9%), hip (14.8%), and shoulder (10.9%). Imaging revealed that 26.9% of flare-ups led to new HO formation within 84 days.

- HO burden: Whole-body computed tomography (WBCT) showed that mean baseline HO volume was 314.4 × 10³ mm³, increasing with age. The highest rate of HO formation was observed in adolescents and young adults (41.5 × 10³ mm³/year in the 15–25-year group).

- Functional decline: progressive joint restriction was observed, with many individuals becoming wheelchair-dependent by their 20s. Cumulative Analogue Joint Involvement Scale (CAJIS) scores increased slightly over 3 years, but the use of assistive devices escalated significantly.

- Respiratory complications: thoracic insufficiency, a leading cause of morbidity, was present in 5.3% at baseline and worsened over time. Forced vital capacity (FVC) declined with age, stabilizing below 50% of predicted values after adolescence.

- Skeletal and growth abnormalities: all patients had great toe malformations; 34.5% had femoral head abnormalities, and 14% had femoral neck shortening. Dense metaphyseal bands (DMBs) were noted in pediatric patients, likely linked to chronic disease impact.

Swellings and protrusions characteristic of FOP (photocredit: Alabama medicine: journal of the Medical Association of the State of Alabama 1984)5

Emerging therapies for Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva (FOP)

Currently, there is no definitive cure for FOP. However, recent advancements in targeted therapies have shown promising potential in slowing disease progression and reducing heterotopic ossification (HO).

- Palovarotene (Sohonos®): a selective retinoic acid receptor gamma (RARγ) agonist, is the first medication approved for FOP treatment. It works by inhibiting cartilage formation, thereby reducing the development of heterotopic bone. Approved in Canada and under regulatory review in various countries, including the United States and Europe.

- Garetosmab (REGN2477): a monoclonal antibody targeting Activin A, a protein involved in the aberrant signaling pathway responsible for HO in FOP.

- ACVR1 inhibitors: since the primary genetic driver of FOP is a gain-of-function mutation in the ACVR1 gene, efforts are focused on developing inhibitors targeting this pathway. Small molecule inhibitors are currently under investigation, aiming to suppress excessive bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling and prevent HO.

- Gene therapy: research is exploring CRISPR-based or RNA-targeted therapies to correct the ACVR1 mutation.

- Anti-inflammatory strategies: Some studies suggest that early anti-inflammatory intervention during flare-ups may mitigate HO development.

FOP: still a long way ahead

While no curative treatment exists, ongoing clinical trials and regulatory approvals mark significant progress in FOP management. Continued research into targeted therapies offers hope for slowing disease progression and improving the quality of life for affected individuals. FOP is an ultra-rare disease, we have yet to understand much about its nature and progression.

Rare Disease Day on 28 February 2025

Since 2008, the Rare Disease Day has been celebrated worldwide at the end of February. esanum covers the day and reports not only on current topics, but also on possible symptom complexes, diagnostics, therapeutic approaches and orphan drugs for the treatment of rare diseases.