Dr. Michele Usuelli: A physician among migrants

A physician recounts his experience at a migrant reception centre in Crotone, run by Italy's Red Cross, amidst bureaucratic red tape and inefficiencies.

Translated from the original Italian version. Michele Usuelli is a physician specialising in paediatrics, and works in the Lombardy Regional Council.

A hands-on experience

I am a physician who is gaining political experience. That is why I try as much as possible to get direct exposure to what I deal with in the halls of political institutions. For the past week I have been the medical director of a large Reception Centre for Asylum Seekers (In Italian known as Centro Accoglienza Richiedenti Asilo or C.A.R.A.) in Crotone, run by the Italian Red Cross. We are talking about one of those places where migrants are transferred immediately after disembarkation.

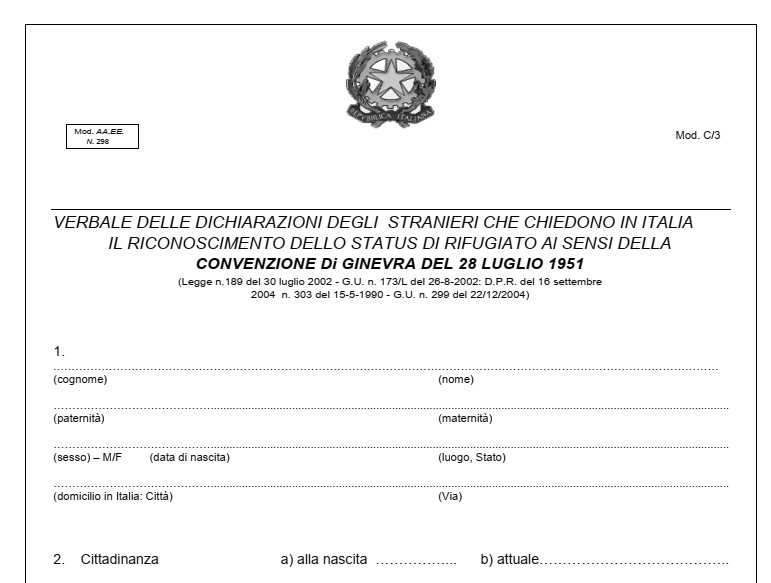

The C3 form: applying for international protection

From a legal point of view, there are two decisive moments for migrants upon arrival in Italy. The first is identification upon disembarkation, where the migrant first manifests his or her willingness to apply (or not) for international protection. The second is the start of the procedure to obtain the C3 Form. In this form, the migrant formally confirms or denies the request for international protection.

A major critical issue is the timing of the C3 Form, which takes place months after the migrant's arrival. Until then, he/she will have no document. Only after obtaining the C3 Form, the migrant will receive a temporary residence permit until the calling of a the territorial commission, which will decide whether to accept the application for international protection.

In the CARAs, adults are allowed to leave during the day and return at night. But the many unaccompanied foreign minors are confined inside the CARA. Without a C3 Form, if you leave, and happened to be stopped by the police, you may be detained until your status is determined.

The slowness in the issuing of C3 Forms fuels illegality, the black market and gangmasters (that engage in illegal recruitment). In fact, it is urgent for the migrant to start as soon as possible to repay the debt incurred for the huge travel expenses as well as for the sustenance of their family members who have remained in the country of origin. One 16-year-old Afghan candidly told me that the journey cost him 12,000 euros...including beatings and torture.

2.5 euro per day

Almost all countries of origin are considered by the territorial commissions to be worthy of some type of protection, with the exception of the so-called 'safe countries' such as Morocco, Tunisia, Senegal, Ghana and Egypt with which there are bilateral agreements with Italy that allow repatriation. The procedure for obtaining the C3 Form requires a 16 euro tax stamp and a passport photo which costs about 5 euro (expenses not provided for in the tender specifications for reception centres) which, according to the prefectures' interpretation of the regulations, are generally borne by the migrant and therefore to be subtracted from the 2.5 euro per day provided to them. It is up to the individual bodies managing the CARAs (as is the case in Crotone) to contract with the prefecture the possibility of using an item in the 'miscellaneous and eventual' expenditure specifications equal to 1.6 euro per migrant per day.

These infamous 2.5 euro per day, to which guests are entitled, in many centres, at the prefectures' discretion, are not handed over in cash, but loaded onto keys. Consequently, they can only be spent at the dispensing machines located in the camp. There is therefore no freedom on the part of the guests to save up the small sums of money or to use them for their future travels, for example, or in the case of Crotone, for a bus ticket, having instead to walk many kilometres on the Ionian highway.

Shared electronic health files, still a utopia

At the Crotone CARA, upon arrival in the facility, all guests receive a code that allows access to certain National Health Service services. In Crotone, an excellent socio-health software is used, which allows the migrant's personal data and socio-health information to be uploaded and viewed. The health file can then be delivered in paper form to the migrant and sent digitally to the other centres where the guest will be transferred. If a centre does not use such tools, the guest will arrive at the next centre without any socio-health information and operators will have to start collecting medical history data from scratch. Adopting a single software for all Italian reception centres would be an easy efficiency revolution in this setting.

About medical care

Those who land on our shores and are received in the CARA often present the classic illnesses triggered by the journey, after travelling in, to use a euphemism, uncomfortable conditions: burns, orthopaedic problems (fractures, sprains - ankle sprains are frequent), scabies, impetigo and various skin infections. Adults also have to deal with chronic diseases, including type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Then there are many children with disabilities, some even presenting rare syndromic symptoms, whom parents entrust to the sea in the hope that they will be cured in Europe.

Then there are many pregnant women. It is not the pregnancy in itself that requires complex care provision, but in these contexts, they need to be looked after extensively to ensure their well-being. Finally, there is no shortage of scars and other outcomes of torture and violence. Psychological and psychiatric discomforts, due both to the situations for which they flee and to the stress accumulated during the journey, represent another important aspect of the assistance that migrants hosted in a CARA need.

In addition to the medical clinic service, there is an asthma service with beds in the infirmary for day hospital and inpatient care. There is a well-stocked in-house pharmacy. In the event of an emergency, the medical emergency system is contacted with referral to the emergency room. The medical officer has a service phone on which he receives calls from CARA personnel and there is an emergency backpack.

There is no 24-hour medical coverage, or nursing. Therefore, during the hours when the health personnel of these managing organisation are not present, even minor situations that could be managed within the CARA often lead to an overload of the city emergency room.

Il Dr. Usuelli in servizio al CARA di Crotone

Hygienic conditions at the CARA

In Crotone, the offices and canteen are in sufficiently clean conditions. The living spaces are not: badly designed, with shared toilets, dirty, and unfurnished.

Many housing modules are unfit for use (e.g. doors and windows are missing), which is why the capacity has been reduced to 641 places compared to the original 1200. However, the uninhabitable modules are sometimes used by guests and deteriorate further. The prefabs that I have seen inhabited are grossly inadequately furnished (mattress bed, or only mattress). The individual housing modules where migrants are housed do not provide for daily cleaning by the company contracted for that service. Cleaning is only carried out in the modules when they are empty, uninhabited, before they are occupied. Nor is there any provision for the reception centre to give the migrants products to clean the accommodation on their own.

Unaccompanied (Foreign) Minors

In Crotone, between 25 and 30 per cent of the CARA guests are unaccompanied foreign minors, who should be given greater protection, but who are the main victims of the reception system's involution.

Unaccompanied minors should stay at the CARA for no more than 48 hours. Therefore, no service dedicated to them is provided. The serious shortage of second reception places for minors means that they are parked in the CARA even for months at a time, without the possibility of leaving the centre (unlike adults) and with nothing to do all day.

If minors need medical services outside the centre, they have to stay with an accompanying person for the entire time of their stay. This wastes human resources and complicates the organisation of shifts with staff already stretched to their limit.

Before the intervention of Interior Minister Salvini in 2020, services aimed at integration and job placement were freely available to asylum seekers. Today, the only second reception service is only accessible if you are a holder of a protection status (which means that it is only accessed after a very long time after entering Italy). Therefore, the fate of migrants is to remain in initial reception centres under the conditions we have described for an average of one year of their lives while waiting for their protection request to be formalised.

A diabetic child patient resumes therapy by showing autonomy in the management of treatment and glycaemic monitoring

No educators or cultural mediators

There is a complete lack of professional educators and the cultural mediators are very few and for very few hours; a total of 42 hours per week.

Language mediation is of fundamental importance for the multidisciplinary team to support the migrants received in order to carry out information and outpatient activities as well as individual interviews with the various professionals, taking into account the multitude of languages spoken by the migrants on site.

Inadequate budgets, poorly written tenders and absence of prefectures

The positive organisational aspects that I have found are only due to the good will of the individual organisations managing the centre's services. The managing bodies that work well do not get enough money from the allocation notices. Those who work badly, on the other hand, make a lot of money. The monitoring of activities, the task of the prefectures, which those tenders allocate, is practically nil. Those who work well are not rewarded, those who work badly, receive no sanction.

The Crotone CARA can accommodate up to 641 migrants and is among the largest reception centres in Italy. All the services and staffing are provided for that number of guests, while in the summer months, due to spikes of migrant arrivals on territorial coasts, peaks of up to 1400 people were reached. The available budget is already low for 641 people, so imagine what happens when the centre accommodates over 1000 people. This situation only allows us to buffer the emergency, without any chance of covering the prerequisites to organise a decent first reception and related care of the migrants received.

There would be so much to improve in order to consider ourselves a civilised country. Instead, the risk seems to be that in the next five years, we will witness a further dismantling of reception services. For this reason alone, I felt it was important to come to Crotone and put down on paper what I experienced.