- Editorial Update: As of January 27, 2020, the case hearing at the Sporting Court of Arbitration was to take place on January 8, 2021, however the hearing has been postponed without a set date.

- This list has existed since 1986. Initially classified by the DCI, it has included the names of relevant specialties since 2001.

- The prevalence of trimetazidine use in athletes in Poland: Excretion study after oral drug administration

- Is trimetazidine (Vastarel) a doping product? Proposal for a deletion from the World Anti-Doping Agency's list of prohibited products

Doping: The challenges of weak scientific evidence

Doping and sports: the topic is always relevant when major international competitions, like the Olympic Games, are taking place.

Anti-doping authorities: "clean" sports at any price?

- Doping tests examine the use of various classes of substances and methods from the World Anti-Doping Agency's (WADA) Prohibited List in athletes and sportspeople

- According to the World Anti-Doping Code (WADC), trimetazidine is one of the classes of hormone and metabolic modulators banned at any time.

- Dr. de Mondenard on trimetazidine: "There are no studies showing that this substance has any doping effect."

Dr. Jean-Pierre de Mondenard is a renowned expert in the field of doping. He does not like cheaters. However, he came to the rescue of a French wrestler sanctioned for taking Vastarel®. The physician denounced a bewildering series of mistakes and asked, along with other experts, a difficult question: what does Vastarel® do on the World Anti-Doping Agency's red list?

Interview by Benoît Blanquart, and translated from the original French version

Dr. Jean-Pierre de Mondenard, a sports physician, has practiced at the French National Sports Institute (Institut National des Sports or Insep) and in his medical practice has been engaged in most of the major cycling events, including three Tours de France. He was also the official physician to the French national judo team. Beyond his home country, his expertise in the field of doping is internationally recognized.

Jean-Pierre de Mondenard does not like cheaters. Yet, he is flying to the rescue of Zelimkhan Khadjiev, a French wrestler sanctioned in 2019 for taking Vastarel®. In the process, the physician denounces a bewildering series of errors for which the athlete is not responsible. Above all, Dr. de Mondenard questions the presence of Vastarel® on the World Anti-Doping Agency's red list. He raises a simple but sensitive question: What is the scientific basis for this listing? This question, despite simple, sends ripples in the anti-doping community.

One thing is certain: Khadjiev's sporting future will be played out before the courts, and the fact that his sport discipline tends to have a low media profile will not help him. Do the anti-doping authorities risk convicting an innocent person if they want to portray the objective of "clean sports" at any costs?

esanum: Dr. de Mondenard, you are defending an athlete sanctioned for doping. Why this decision?

Dr. de Mondenard: For more than 50 years I have been a staunch opponent of doping. I was one of the first physicians to perform tests during cycling competitions. I have no complaisance towards dopers. But on the other hand, I do not accept that an athlete should be sanctioned without a reason.

Doping is a complex, sometimes troubled universe with many conflicts of interest, but all I am interested in is its scientific dimension. To "drop" a doped athlete always seems a good thing, but it still has to be scientifically justified. Before talking about the Khadjiev case, I will give you an example of the mistakes of the anti-doping fight.

In 1988, the French junior cycling champion Cyril Sabatier, 18 years old at the time, tested positive for testosterone. He swore that he was innocent, and I had finally understood that he was right. At the time, to quantify testosterone, the relationship between testosterone and epitestosterone dosages was established. This ratio is normally 1, usually with a maximum of 6, so the biological experts said, "Above 6 is doping". Cyril Sabatier was at 8.1.

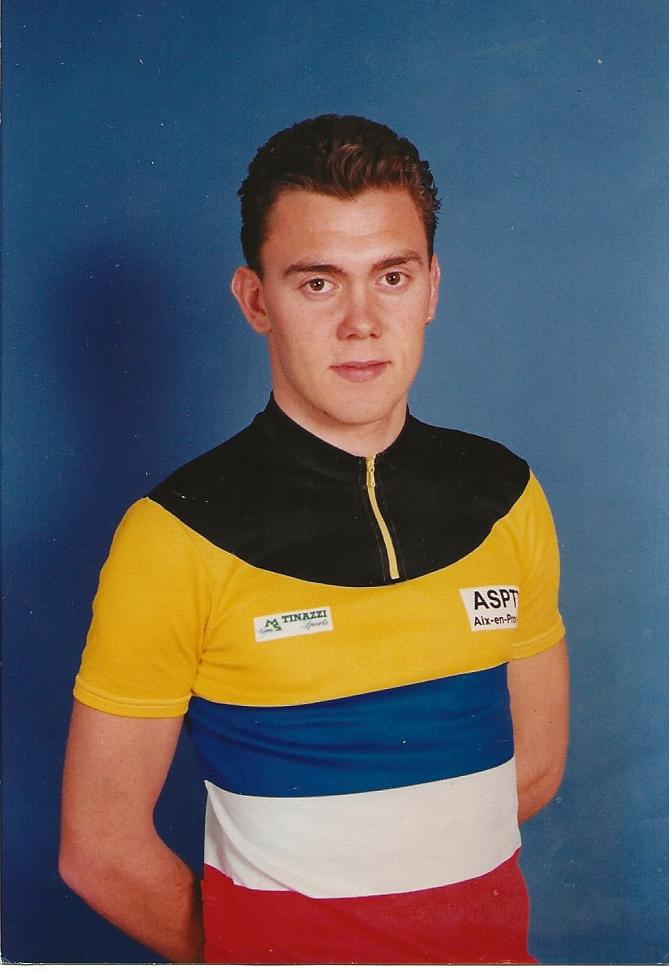

Cyril Sabatier (DR)

At the time I first wanted to redo the urine analysis. Strangely, the bottle had been broken. I then went to a private hormone laboratory. On that occasion, the person at the laboratory had performed a 24-hour urine test on about 20 top athletes, who were also 18 years old. I managed to reach a conclusion. At that age testosterone can be high and epitestosterone low, which distorts the outcome of a report. It took years for the IOC to take this physiological aspect into account. Julien Bonétat, a French squash champion, was sanctioned for the same reason, then rehabilitated years later.

In fact, both Sabatier and Bonétat naturally exceeded the threshold of 6, while athletes with a natural testosterone/epitestosterone ratio of 1 could dope themselves up to the threshold of 6 without being caught at the doping control. The current method of measuring exogenous and endogenous testosterone dates back to 1993. For example, the gaps that existed in scientific testing brought down cyclist Floyd Landis in 2006. Sabatier and Bonétat were innocent. In the case of Zelimkhan Khadjiev, if someone can prove to me that the substance he took improved his performance, I will stop defending him on the spot.

Zelimkhan Khadjiev (DR)

esanum: What happened with Zelimkhan Khadjiev?

Dr. de Mondenard: Khadjiev is a French freestyle wrestling champion. Twice medallist at the European championships, he participated in the 2016 Olympic Games. His bronze medal at the world championships in 2019 was taken away from him because of this case.

In early September 2019, due to intensive and repeated training in his preparation for the World Championships, he was suffering from leg pain. On the advice of a coach, he went to a pharmacy to obtain Vastarel® (trimetazidine). Khadjiev trains at the INSEP complex located in the Bois de Vincennes (France). So he went to the nearest pharmacy, the one where all the athletes training at the INSEP go to. The succession of mistakes made afterwards is astonishing.

First, the pharmacist agreed to dispense trimetazidine without a prescription, even though the substance requires a prescription from a cardiologist since 2017. Then, he checked the Vidal (French medical company) leaflet in the box to see if the words "warning to athletes" appeared. It was not there. However, trimetazidine has been on the World Anti-Doping Agency's (WADA) "red list" since 2014, which the French National Drug Safety Agency should have portrayed in the Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC). This was the second error.

Trimetazidine, did appear in the red list of doping substances that Vidal printed in its warnings1. But in 2019, for the first time, this list was no longer available as a paper version; the pharmacist should have consulted it on the company’s site Vidal.fr but did not. As a result, Khadjiev received a four-year suspension from all competitions and the French Anti-Doping Agency (French acronym: AFLD) even banned him from training at the INSEP with other wrestlers of his level. All this for a substance that does not even improve performance.

esanum: Why is trimetazidine on this red list?

Dr. de Mondenard: That's what I would like to know. I have asked the WADA, which issues this list. I did not get an answer. There are no studies showing that this substance has any doping effect. When in July 2020 Khadjiev went before the disciplinary chamber of the International Wrestling Federation - which expelled him - his lawyer asked WADA to produce scientific proof of the doping nature of trimetazidine. WADA provided a 2014 Polish study2 showing that it was possible to find the substance in the urine of volleyball players. This put the effectiveness of the laboratory into question, but said absolutely nothing on whether trimetazidine improves performance.

The only other study available is the results of the tests carried out in Sochi during the 2014 Winter Olympics: out of 2,134 urine and 479 blood tests, trimetazidine was found only once. I would point out that trimetazidine does not mask the doping effect of another substance either, in which case it would appear in a specific paragraph of the list of illegal products.

The World Anti-Doping Code, which is enforced by WADA, has set three criteria for a product to be on this red list. It must enhance performance, which in this case there is no evidence of. It must present a proven or potential health risk, which is the case for any drug. Finally, it must be "contrary to the spirit of sport", therefore taken with the intention of improving results. Even a placebo can meet this last criterion. These three conditions raise questions.

When it was placed on the Red List in 2014, WADA explained that trimetazidine was one of the "emerging modalities of doping". We are talking about a substance that has been on the market since 1964... In fact, when a substance that is authorised but diverted from its therapeutic indications appears to be more widely used by athletes, WADA can put it "under surveillance". For example, if it is found more and more often during testing. This is often the first step before it is put on the red list. Trimetazidine has never been placed under surveillance.

In 2014, trimetazidine was first classified as a "specific stimulant" and therefore prohibited only in competition. In the event of a test, the sanction could be reduced or even cancelled if the athlete in question showed that he or she had not taken it to improve his or her performance. But in 2015, without any supporting scientific studies, trimetazidine was reclassified in the category of "non-specified metabolic and hormonal modulators", because of its supposed action on cardiac metabolism. As a consequence, it is now prohibited even out of competition. At the first offence, the athlete is banned for four years.

Why this red list classification in 2014 and this change of category in 2015? It is a mystery, and in the absence of an explanation, we can only hypothesise that trimetazidine was banned because of its similarity to another substance without any scientific work validating this change of category.

I am not alone in questioning the presence of trimetazidine on the red list. Pascal Kintz is professor of toxicology at the University of Strasbourg (France). He is a leading expert and a judicial expert at the Court of Cassation (esanum’s note: In France, the “Cour de Cassation” is the highest court in the French judiciary). In the editorial note3 of the latest edition of the French scientific journal Toxicologie analytique et Clinique, he describes the mechanism of action of trimetazidine as "not yet fully established" and recalls its damaging side effects that would be of crucial impairment for a sportsperson: drop in blood pressure and parkinsonian-type effects. Professor Kintz even writes: "It appears to be illusory to want to find an interest in improving performance with trimetazidine".

esanum: Four years of suspension is quite a heavy sanction. Are all sportspeople subject to similar rulings?

Dr. de Mondenard: In theory, yes. But in fact everything is played out before the commissions of international federations or before the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) in the event of an appeal. Here, a sportsman like Khadjiev does not have the same chances as a Christopher Froome, for example. Khadjiev practices a sport with little media coverage. He is defended by the lawyer of a national federation. Froome, suspected of doping with salbutamol in 2017, was defended by the lawyers of his Sky team and its sponsors. Otherwise, the cyclist would have been stripped of his victories in the 2017 Tour of Spain and the 2018 Tour of Italy.

Team Sky was successful in cornering the International Cycling Union (UCI) and WADA from the very first hearings in the anti-doping commission. Its lawyers simply said: "Give us the study proving that Froome, after three weeks of racing and at a rate of 200 km per day cycling, cannot naturally exceed the set threshold." That threshold was 1,000 ng/ml, Froome reached 2,000. WADA released a 20-year-old study on swimmers, when the effort is not at all comparable. The UCI dropped the case and Froome was cleared.

When the Froome affair broke, the scandal was huge. I knew that the factor to be taken into account was his urinary density. A factor that changes everything. I had defended a few years before the cyclist Éric Berthou, who showed a salbutamol level of 1879 ng/ml in a control. He had also been cleared because I had explained that if you cycle for five hours in very hot weather, you get dehydrated so your urinary concentration increases. I'm not saying Froome didn't dope. I'm saying that he may have naturally exceeded the WADA threshold for salbutamol.

For Khadjiev, I find that in the absence of proof of doping the sanction is far too severe. Especially when we see that the athlete from the Kingdom of Bahrain Salwa Eid Naser, 400 meters world champion, has just been cleared by the International Athletics Federation. Yet she has failed four doping tests, which for experts says a lot about the high probability that she was on anabolic steroids. The Athletics Integrity Unit announced on November 12 that it is appealing the case to the Court of Sport Arbitration.

esanum: What lies ahead for Zelimkhan Khadjiev?

Dr. de Mondenard: Everything will unfold in Lausanne (Switzerland), at the CAS, because his lawyer has appealed the decision of the International Wrestling Federation. He asked for a public trial, and for WADA to come and explain itself, something that they refuse to do at the moment. The hearing will not take place until 2021, an unusually long time. I have the impression that the WADA is hindered in its efforts to get itself out of this situation.

I believe that when the fight against doping is caught in the balance, WADA is stubborn. Even if it means punishing innocent people. There are also issues that go far beyond this wrestler's history, but which he may be indirectly responsible for. The world of anti-doping is small, but the interests are colossal. The Canadian judge who convicted Khadjiev at the International Wrestling Federation hearing is also an advocate for some athletes, and he practiced professionally for four years with WADA.

In addition, since 2018, WADA has been in competition with a new agency, the International Testing Agency (ITA), supported by the International Olympic Committee. In two years, the ITA has succeeded in becoming the official anti-doping agency for 45 international federations, including the wrestling federation. If it can be proved that the red list contains a substance with no doping effect, WADA will be further weakened. This is Khadjiev's only hope for a revision of his suspension.

It is therefore the ITA that is investigating the case between WADA, its rival, and Khadjiev. But the common goal of such bodies is the same: to sanction as quickly as possible, and to herald the image of "clean sports”. Athletes are not a priority.

Notes

Further Resources

- For further information, we suggest the following selection of French-language resources from Dr. Jean-Pierre de Mondenard's blog, and about Vastarel® in particular:

- Jeux olympiques d’hiver - Une bobeuse russe épinglée à la trimétazidine.

- C’est quoi ce truc ? Produit lourd ou pétard mouillé ? (26 février 2018)

- Dopage ton histoire - Aucune étude scientifique ne prouve que le Vastarel® est un produit dopant… Pourtant après un contrôle positif des sportifs sont lourdement sanctionnés. Cherchez l’erreur… (11 juin 2020)

- Dopage - Zelimkhan Khadjiev, un lutteur français, se défend d’avoir cherché à se doper avec du Vastarel® Décryptage (08 juillet 2020)

- Cas positif à la trimétazidine du lutteur Zelimkhan Khadjiev versus l’AMA - Visiblement l’AMA ne lutte pas contre le dopage mais contre ceux qui dénoncent son impéritie ! (11 septembre 2020)

- Lutte antidopage - La mascarade des instances - Bavures, injustices, mépris… Des décisions incohérentes prises par des officiels dits indépendants - Deux poids, deux mesures (1er novembre 2020)