Organ donor heroes: we need more like them!

In her column, Dr Yildiz talks about the courageous relatives of organ donors, innovative surgical techniques, and life-saving cross-over living donations.

The Organ Donation Blog

By Dr Ebru Yildiz

Organ donation: Relatives are heroes too

This morning I had an experience that showed me once again that I would like to honour organ donors and their relatives more. They are hidden heroes that nobody sees and nobody talks about. I see this especially in those relatives who had to make a decision because their donor hero had not made a decision beforehand and left it behind. Why is this so important to me again?

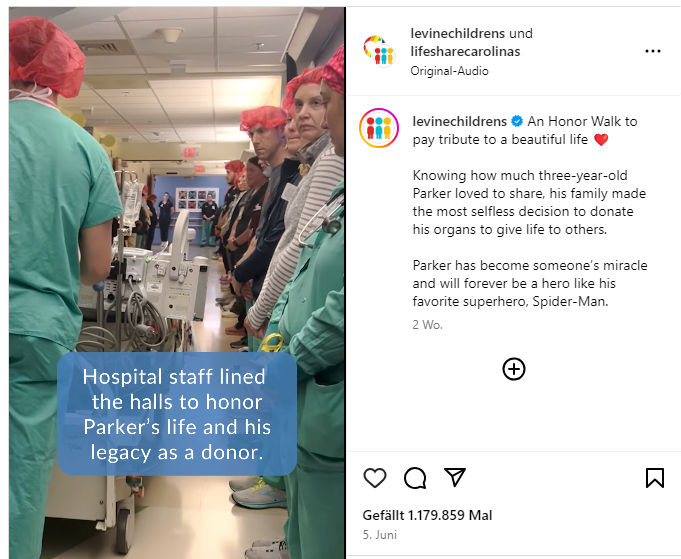

Because this morning I saw a moving video with a little hero and his family. A deceased little boy was lying on the bed in his Spiderman costume with his mum next to him. They were driven through a hospital corridor in the USA - and the entire staff stood guard. The relatives accompanied the little donor behind the bed to the operating theatre. It was only 30 seconds on Instagram, but it was very moving. The child had apparently died of brain damage and the parents had decided in favour of organ donation.

The video made me think once again that these people who make such decisions are far too little appreciated and emphasised. They are lifesavers! And they don't just save someone else's life, they save entire families who can keep their father, mother, brother or sister with a donor organ. We only ever see the recipient who receives the organ. But there are so many other stories around it. Hendrik Verst, a liver transplant influencer, described this beautifully in his book ‘I promised you I wouldn't die’ (In German: Ich verspreche dir: Ich werde nicht sterben). His four children were also given a life with the donor organ, a life with their father.

Many people are moved by this, but only a few decide to become organ donors themselves. The so-called opt-out solution is currently being discussed again in order to advance the topic of organ donation and transplantation. The objection solution alone will not be the way forward. I would also like to see more education, more awareness, more realisation and more voluntary decisions to become a donor hero if the worst comes to the worst.

Cross-over living donation

At the same time, I am currently concerned with the topic of cross-over living donation. [In Germany] there is a draft bill on the table that would make it possible for people other than close relatives and life partners to be donors. However, living donation is very strictly regulated by law. The donor may only donate to a family member of the first or second degree or to a person with whom they have a demonstrably close emotional bond. So it can't be the friend I've known for six months. That often doesn't fit. The idea here is to expand this: living donors whose organs are not suitable for their relatives or partners are collected in a pool.

In this way, their organ(s) could be given crossover to someone suitable, while their own relative then receives an organ from someone else. This would significantly increase the number of transplants. This could open up a new path for donor couples who are incompatible, i.e. immunologically unsuitable. Progress in living donation naturally concerns me a great deal, because if post-mortem donor organs continue to be in such short supply, this may provide some relief.

The development of gentler surgical methods

Fortunately, great progress has been made in surgical technology. At Essen University Hospital (Essen, Germany), organ removal is performed endoscopically. This saves large incisions. But I also know that there are much gentler techniques. In Turkey, for example, there are significantly more living donations than in Germany - 53 living donors per million inhabitants. In Germany, we have a total of around 600 a year. Due to the greater willingness to donate in Turkey, better techniques have been developed and trained over time in a centre that operates on 150 living kidney donations a year. This means that they have an operation there every other day. Now they no longer need a visible incision to remove a kidney from women. There is a small incision through the navel for the endoscope and other devices. And the kidney is then removed vaginally using a sterile endobag.

Operating theatres with the help of robotics

And of course we also want to achieve such progress elsewhere. For example, we are now performing so-called da Vinci operations at our transplant centre. This was previously only used in gynaecology and urology. Now we are also operating with robotics for living liver donation. The surgeon controls the devices using controllers. This means significantly fewer, smaller and more precise incisions, which means smaller wounds, less pain and faster healing.

And this is where the circle closes: we need practice for such innovations. So more organs, more transplants, more manual practice. All in all, more innovation in medicine. In the end, we can help more people and improve their lives.

A short biography of Dr Ebru Yildiz

Dr Ebru Yildiz has been Head of the West German Centre for Organ Transplantation (In German: Westdeutsche Zentrum für Organtransplantation) in Essen since 2019. While a specialist in internal medicine and nephrology, she has additional training in transplant medicine and internal intensive care medicine.