- Rowe I. Clinical MASLD pathways in 2030 – what, who and where?. EASL 2024. Thursday, 6 Jun, 08:30 - 09:45 CEST

Management of MASLD in 2030

Which diagnostic and treatment pathways for MASLD patients will exist in 2030? Dr. Ian Rowe discusses patient management scenarios in the near future.

Who, where, how

Hepatologists are addressing MASLD (liver disease associated with metabolic dysfunction) as a noncommunicable disease at the population level. Most noncommunicable diseases are managed in primary care, not by specialists. Family physicians should already be able to prescribe therapies to patients with MASLD that can improve quality of life and decrease the risk of liver complications. If this is not happening today, perhaps the medical community needs to work to make diagnostic and treatment pathways simpler, easier to understand, and better for both patients and clinicians.

MASLD in primary care

In primary care, there is great familiarity with the management, diagnosis, and treatment of common noncommunicable diseases. Take cardiovascular disease, for example, which is highly prevalent and has a well-understood risk, especially in patients >50 yr and particularly in men. Atherosclerosis need not be diagnosed to treat the disease; the risk of future events is worked on and preventive treatment such as statins is offered. Similarly, for type 2 diabetes, a screening or diagnostic test such as HbA1c is used and monitored for complications such as retinopathy and nephropathy, giving guidance for lifestyle modification.

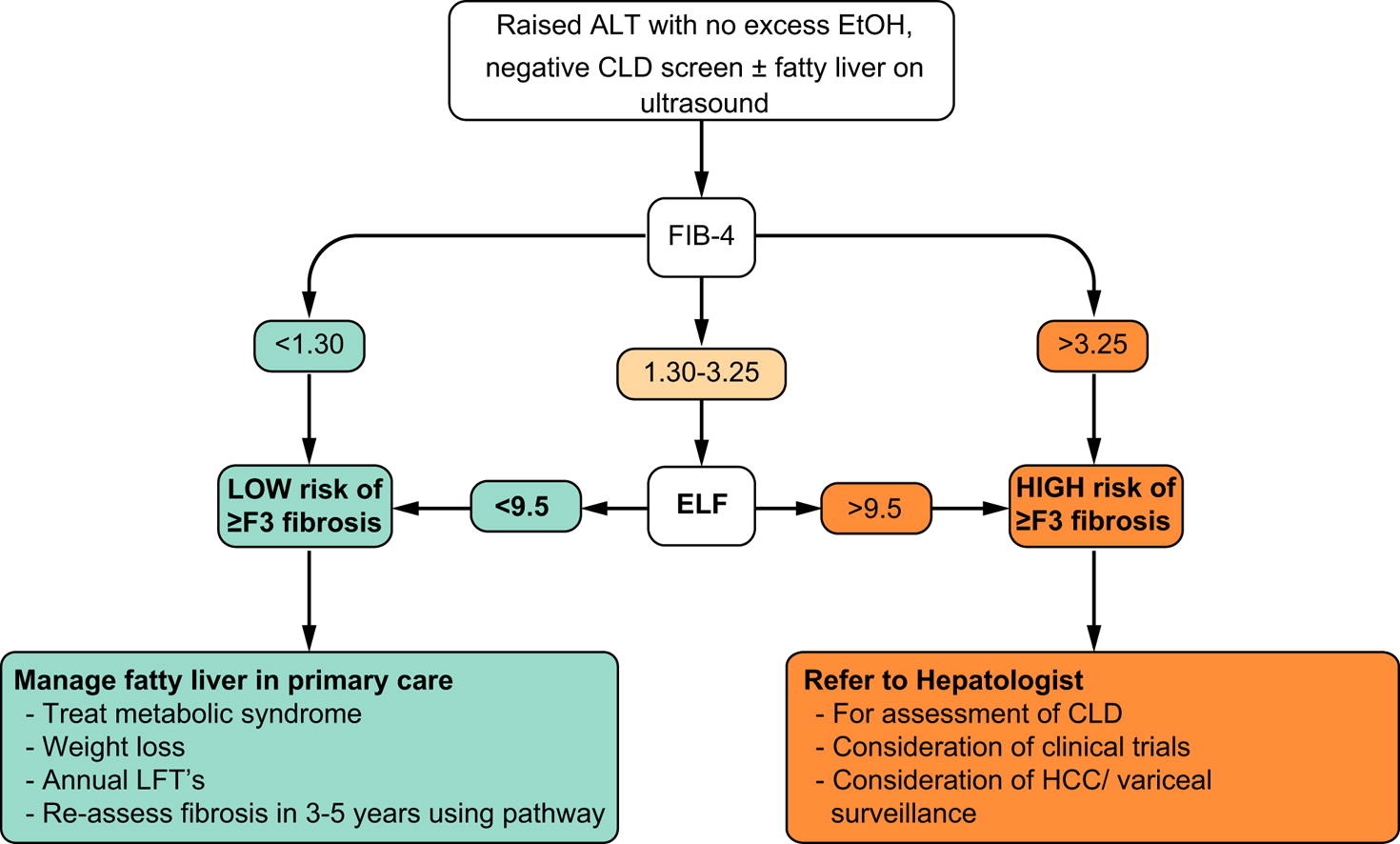

Speaking of MASLD, there are many similarities with other noncommunicable diseases: we have a specific population at risk (overweight or obese people, type 2 diabetes), we have screening tests (liver ultrasound) and risk stratification tools (FIB-4 score, ELF, LSM). One could immediately intervene with indications related to diet and physical activity to avoid complications such as HCC and organ failure. However, primary care physicians are less comfortable with the management of MASLD. How can this be made easier for them?

Simplify the diagnostic process

First element to consider: whether it is really necessary to know if steatosis is present. Steatosis is the hallmark of the disease, but it doesn't really help to know that you have steatosis without fibrosis, as the treatment remains the same: lifestyle changes, i.e., improving diet and exercising. Hepatic steatosis is not ruled out by a negative ultrasound, so there is no need to confirm it before risk stratification.

Today the tools exist to do risk stratification in primary care. Several studies have identified ways to identify patients at risk for advanced fibrosis using noninvasive tests (NITs) and refer them to secondary care. The goal is to predict liver-related events, not just advanced fibrosis. For example, the Liver Risk Score uses biomarkers to predict liver-related events and shows good performance in predicting these events.

A major concern in primary care is about false negatives in noninvasive tests. Although false negatives are considered unacceptable in liver disease, they are the norm in other diseases. However, it should be mentioned that noninvasive tests, such as the liver risk score, are improving in predicting events.

Toward 2030 with greater simplicity

The seminar concluded by speculating that, in 2030, the population at risk will remain the same: people who are obese, have type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and other metabolic disorders. But it will no longer be necessary to confirm steatosis before fibrotic risk stratification. Individual risk prediction will be simplified to decide who remains in primary care and who is referred for treatments. Emerging treatments will be evaluated for cost-effectiveness and quality-of-life improvement.